Text © 2008-2024 Kevan Hashemi

Illustration © 2009 Susky Hashemi

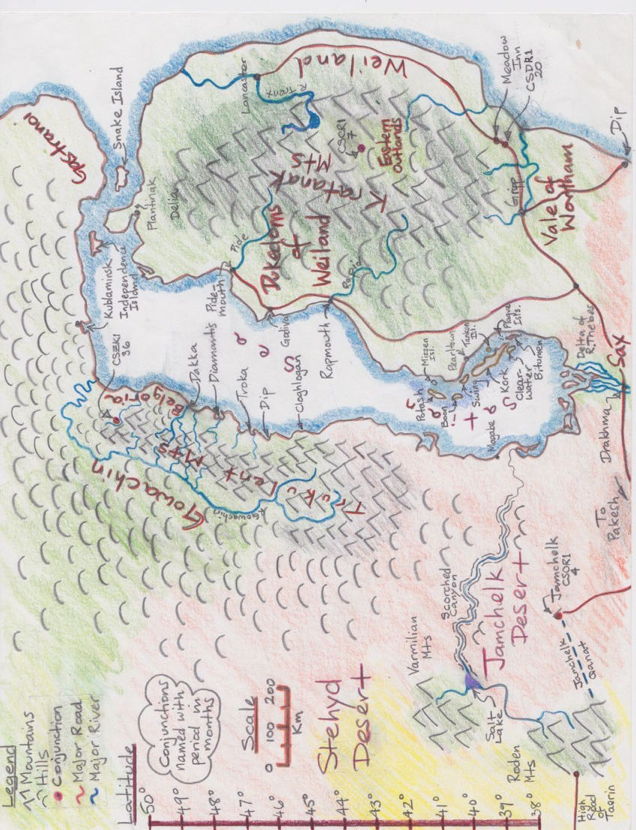

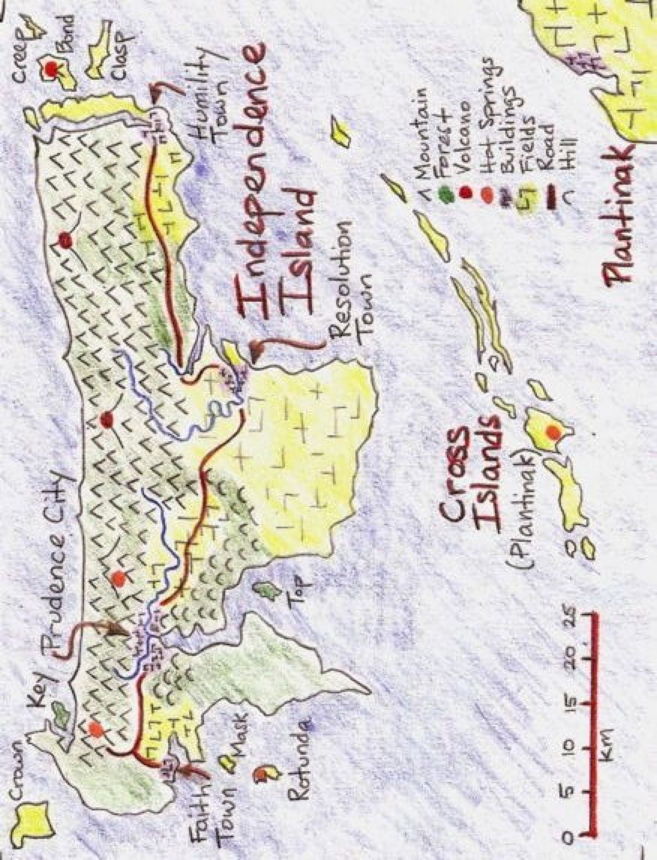

Maps © 2008 Kevan Hashemi

Cover © 2024 Kevan Hashemi

Sallina was eighteen years old. On most days, she worked on the farm where she lived with her parents and her brother. On other days, she walked into town with a shopping list. When it was sunny and hot, she walked to town through the forest on the hill. This forest belonged to the Duke, and one of his laws was, "Anyone who lives here may walk through my forests, but everything in the forests belongs to me." On one particularly sunny afternoon in mid-summer, Sallina was walking through the Duke's forest with an empty basket on her arm, when she saw the woodcutter and his son through the trees. She left the path and walked towards them.

Garibaldi, the woodcutter's son, had been cutting down trees with his father all afternoon. Their two horses had been pulling out the stumps with ropes. The last stump of the day lay beside a big hole in the ground. As Sallina approached them, Garibaldi's father mounted one of the two horses. He nodded at Sallina, smiled at Garibaldi, and said, "I'll see you later." He turned his horse and trotted away.

Garibaldi patted his the other horse on the neck. "Good girl, Eliza." He knew that Sallina, the farmer's daughter, was walking towards him. He folded his arms. You might think it would be more polite for Garibaldi to say "Hello, Sallina". But Garibaldi was not sure he wanted to speak to Sallina. Sallina said clever things that made him feel foolish. Garibaldi did not like to feel foolish. He certainly did not like to feel foolish in front of Sallina.

Sallina stopped next to the tree stump and smiled. "Hello, Garibaldi."

Garibaldi nodded.

"Did you chop off your tongue with your axe today?" she said.

There, you see? She was making fun of the fact that he had not said Hello. Garibaldi shook his head.

"Are you sure? Why don't you show me that you still have it, so I can relax."

Garibaldi raised one eyebrow. He was proud of the fact that he could raise one eyebrow. When he raised one eyebrow he meant, "What are you talking about?"

Sallina stepped closer to him and pointed at his eyebrow. "There's that tick of yours again."

Garibaldi frowned.

"You know, the eyebrow thing."

What could a young man say to such a woman?

Sallina smiled. He didn't talk much, this woodcutter's son, and that was, she thought, a good thing in a young man, because most young men never stopped talking. They would tell her all about the clever things they did at school, or how rich they were, or how good they were at swimming. Garibaldi hardly said anything. But everyone liked to watch him cutting down a tree, especially when it was hot and he took his shirt off. The last time Sallina was in town, Garibaldi had been cutting down a tree outside the town hall and a crowd of young women had gathered to watch him. Sallina was there too. She had even pushed another girl out of the way so she could see better. Every cut Garibaldi made with his long axe bit deep into the tree and, much sooner than they would have liked, he cried, "Timber!" and the tree came falling down.

"I haven't chopped off my tongue," Garibaldi said.

"Oh good!" Sallina said. She smiled at him. He said nothing. She looked at the tree stump. "What a big tree you cut down, and what a big stump you pulled out of the ground."

"The horses pulled the stump out of the ground," Garibaldi said. He frowned and looked down at his boots. That was a silly thing to say. Of course the horses pulled the stump out of the ground.

Sallina was thinking how Garibaldi never boasted about anything. When he kept frowning at his boots, she looked at the hole where the tree's roots had been. The earth was dark and damp in the hole. There were little bugs crawling around in the dirt, all confused by the great movement of the tree stump, and trying to find new places to hide from the birds. And there, in the dirt, was something shining. It was a small coin. It was a gold coin.

"What's that?" she said, even though she knew what it was. She put her shopping basket down, stepped into the hole, and picked up the coin. As she did so, she saw several others. "There are gold coins in here!"

Garibaldi stepped closer to the hole. Sallina handed the coin up to him. He looked at it. He put it between his teeth and bit it. The metal was soft. "It's gold."

"Were you looking for gold?" Sallina said.

"No."

Garibaldi stepped down into the hole next to Sallina. They turned over the dirt and picked out more gold coins and collected them in their hands until Garibaldi uncovered a glistening pile of coins in a small chest.

"Gosh," Sallina said.

They crouched in the dirt and looked at the shiny coins. The chest was small, but it held hundreds of coins, maybe thousands. A thousand gold pieces was enough to buy a farm, or a fine house in the town. There was a wooden lid in the dirt nearby. Sallina picked it up and shook the dirt off it. Some little metal pieces on the side of the lid had turned to brown powder from being buried in the wet earth. The wood was cracked in places, and stained black, but it was still strong.

Sallina put the lid on the chest, just to see if it would still fit. It did. She took it off again. She reached into the chest and picked up a handful of coins. They were heavy, which she expected, but they were also warm, which she did not expect. The coins sat in the palm of her hand, warm, and heavy. She wanted very much to put them in her pocket and keep them for herself.

"What shall we do with them?" she said.

"What do you mean, what shall we do with them? It's in our hole. What shall I do with them?"

"This is the Duke's forest, so the gold, according to the law of the land, belongs to him, just like the trees, and the mushrooms, and the deer, and everything else in the forest."

Garibaldi had to admit to himself that Sallina was right. The gold belonged to the Duke. He looked around to see if anyone was watching them. He could not see anyone, but it would be easy for someone to hide in the shadows beneath the trees. He looked at the gold. There was so much of it. He and Sallina would be rich if they kept it. But if the Duke found out, they would both go to jail. Could he trust Sallina to keep the gold a secret, or would she tell her friends? If she told her friends, would they keep the secret? No, they would try to get some of the gold for themselves by saying, "Give me some of the gold, Sallina, or I'll tell the Duke that you stole it." On the other hand, Sallina was no fool. Perhaps he could make her promise to tell no one at all, not even her own mother, and she would keep her promise.

When Garibaldi looked around to see if anyone was watching, Sallina did the same. She saw no one. Was this a trap? Did the Duke bury the gold under the tree to find out what they would do? No, someone had buried the gold here a long time ago. The lock and the hinges on the chest had rusted away to nothing. The chest must have been buried for a hundred years. Whoever buried it had died long ago. Only she and Garibaldi knew the gold was here, and they could share it between themselves. She knew she could keep a secret, but could Garibaldi? Even if he could keep a secret, he might use his gold to buy himself a thick fur coat, or a fine silk shirt. The Duke would see Garibaldi wearing his new clothes and ask where he found the money to buy them. The Duke could be frightening when he was with his soldiers. If Garibaldi was frightened enough, he might tell the Duke about the chest, and about how he found it with Sallina in the Duke's forest. The Duke would take away the gold and throw them both in jail.

Sallina remembered something her mother always told her, "Money is the root of all evil," which meant that people often wanted money so badly that they would do terrible and stupid things to get it. Would Garibaldi try to kill her so she could never tell the Duke about the gold and he could keep it all for himself? She looked at him. He looked at her. No, Garibaldi would not hurt her. He was a good man, not a murderer. She was being foolish. Trying to keep the gold was foolish, too. It belonged to the Duke.

"We should take it to the Duke," Sallina said.

"I suppose we should," Garibaldi said. He gathered up the loose coins and put them in the chest. Sallina put the lid on. Garibaldi picked up the chest. The gold was heavy, but he could lift it easily with his strong, woodcutter's arms. "Let's go to the Duke right away. Maybe he will give us some kind of reward for finding the chest."

Sallina nodded. That was probably the best thing they could do. They put the chest of gold in one of Eliza's saddle bag and started off down the hill, through the trees, towards the town. Garibaldi lead Eliza by the reins and Sallina walked beside him. When they had gone fifty paces, Sallina said, "Perhaps we should not go through the town. We will see a lot of people there, and they will ask us what we are doing. Somebody might try to take the gold from us before we can bring it to the Duke and get the reward. They might try to get the reward for themselves."

Garibaldi stopped walking. Sallina and Eliza stopped too. He nodded. "Good point. Let's go along the top of the hill and come down on the far side of his estate. That way nobody will see us."

They turned Eliza around and walked up the hill. A breeze rustled the leaves above them and the sun shone down in little spots upon the forest floor. They walked side by side but they said nothing to one another. When they reached the top, Garibaldi heard a twig snap on the ground behind them. He stopped and turned around. Sallina did the same.

"What is it?" she said.

Three young men stepped out from among the trees. They wore hunting clothes made of fine wool and leather. They walked towards Sallina and Garibaldi. They were smiling, but Sallina did not like the smiles on their faces. She knew these three young men. Everyone knew them. They were always getting into mischief, but never seemed to get into trouble for it. Somehow, it was always the people around them who got into trouble.

"What have we here?" one of them said. His name was Lawrence Matthews. He was the son of the richest man in town.

"Two love birds walking alone through the Duke's forest?" another one said. He was the eldest son of the judge.

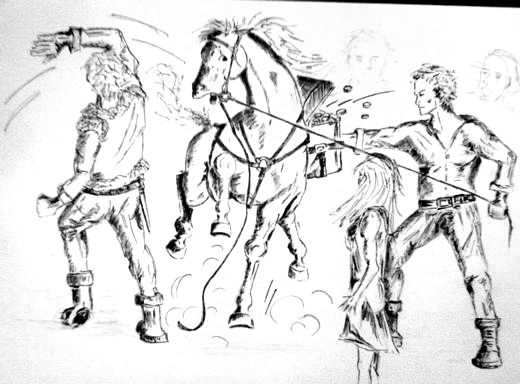

By this time, the three young men were only a few paces away. The third young man, who was the judge's younger son, jumped forward and slapped Eliza hard on the bottom.

Eliza did not like being slapped on the bottom. She reared up on her hind legs, pulled on her reins, and whinnied. Her saddle bags flew up on either side of her. The chest of gold slid out of one of the bags and fell through the air. When it landed, its lid came off and the gold coins spilled out across the ground.

The three young men stared at the gold.

"What's this?" Lawrence said, "Stealing gold from the Duke's house while he is away?"

Sallina frowned. "He's not away, is he?"

"As if you didn't know," Lawrence said, "I think we should take that gold back for him, don't you, boys?"

"Indeed we should," they said. They moved forwards.

Sallina stood over the gold and raised her fists. "No you won't!"

Garibaldi had been so surprised by the three young men coming out of the trees, and by one of them slapping Eliza on the bottom, and by the gold spilling across the ground, that he had been standing still, not knowing what to say or do. But when the young men walked towards the glittering pile of coins, and Sallina raised her fists to fight, he let go of Eliza's reins and stepped forward.

Lawrence did not see Garibaldi coming up beside him. Garibaldi struck him hard on the side of the head with the palm of his hand.

"Oh!" Sallina said.

The judge's sons stopped moving towards the pile of coins and turned to see what had happened. Lawrence swayed upon his feet with his mouth open and fell to the ground. The judge's sons looked at Garibaldi and at Lawrence. Garibaldi took a step towards them.

"Let's get out of here," the older one said.

They turned and ran. They ran off down the hill through the trees. Garibaldi watched them disappear into the forest. When they were gone, he looked down at Lawrence. Lawrence opened his eyes and blinked. He rolled onto his knees and stood up. His face was red and his mouth was twisted into an ugly scowl.

"Sneak," he said.

Garibaldi put his arms on his hips. Sallina stood over the pile of coins and held her breath. Lawrence jumped forward and swung his fist at Garibaldi's face. Garibaldi moved his head back a little and Lawrence's fist flew through the air without touching him. Garibaldi took a step forwards and punched Lawrence in the stomach.

"Ugh!" Lawrence said. He bent over and held his tummy.

"Get lost!" Garibaldi said.

Lawrence moved backwards. When he was ten paces away, he turned and started jogging down the hill. He could not go very fast because he could hardly breath. Sallina laughed.

Lawrence stopped and turned. "You'll be sorry for this! The Duke will hear all about it from me, and then the both of you will be eating bread and water in jail for years!"

He took a few more steps and turned again. He raised his fist and shook it. "For years, I tell you!"

Sallina did not laugh. Lawrence jogged down the hill and disappeared into the trees.

Sallina left the pile of coins and took hold of Eliza's reins. Garibaldi knelt beside the coins and began picking them up and putting them in the chest.

"Well," Sallina said, "You're a good man to have around in a fight."

When Garibaldi could find no more coins among the leaves and dirt where the chest had landed, he lifted the chest and carried it to Eliza. He put it in the saddle bag and strapped the bag shut. He had forgotten to strap the bag shut the first time.

"What do we do now?" Sallina said.

Garibaldi rubbed his hand. It hurt from hitting Lawrence on the side of the head. He was glad he had not hit Lawrence with his fist. He might have broken his fingers.

"I don't know. Those guys will say we were not going to the Duke's house, and you know how everyone believes them."

"But we were going to the Duke's house!"

"Yes, I know that, and you know that, but the truth is that we were going away from his house, and planning to go towards it later. You know the Duke. He is nice enough most of the time, but when it looks like someone's trying to cheat him, he gets pretty angry. And he'll probably believe those idiots when they tell him that we were trying to run away with the gold. They're rich, and we're not. It doesn't matter what I say, I'm just the woodcutter's son."

Sallina nodded. "And I'm just a farmer's daughter." She had never heard Garibaldi say so many words at one time. And what he said made sense, too. But she did not want to believe it, because if he was right, then she and Garibaldi were in a lot of trouble. They might spend a year in jail, even if they took the gold right away to the Duke's house. Most likely, if the Duke was away, they would be thrown in jail until he came back, and sometimes he was away for weeks.

"We don't have much time," Sallina said, "It will take them ten minutes to reach the town, and another twenty for the police to get here and start following us. We must go now to the Duke's house and be ready to spend several weeks in jail, or we must run."

"It's a lot of money," Garibaldi said, "If we run, we can keep if for ourselves."

"Can we? Or will you keep it for yourself and leave me alone somewhere in the forest?"

"You could do the same to me."

"But I wouldn't."

"Nor would I," Garibaldi said.

They looked at one another.

"We don't have much time," Sallina said.

"What do you want to do?" Garibaldi said, "Tell me, and I promise I will not tell the Duke."

Sallina looked at the saddle bag. She could see the shape of the chest inside. There was a lot of gold in there. If they ran with it, she might never see her family again. But if they did not run with it, she might spend a year in jail. If they ran with the gold, they might be able to find a safe country to live in, and she could buy a farm with her share of the money, and her family could move there and live with her. Was Garibaldi really willing to go on such an adventure? It hardly seemed possible. Her heart was beating so hard she could hear it thumping in her chest. Her hands and her forehead were sweaty and cold at the same time.

"I'm scared," she said.

"Me too," Garibaldi said, "But my father has often told me that chances," he rubbed his chin, "opportunities, they come at the strangest times, and we should never say no to them just because we are scared. I don't want to go to jail. Here we have enough money to make our fortune in another country. So let's try it. I may not see my father again for a long time, but he will understand, and I think he will be proud of me for trying."

"Aren't we just being greedy and stupid?" Sallina said.

"We were not greedy and stupid when we found the gold, only when we met three stupid people who are going to go and tell the judge that we were trying to steal from the Duke, and the judge is going to believe them. He always does. They're his sons."

Sallina looked at Garibaldi. How exciting it would be to go on an adventure with him. She laughed. "Okay, Garibaldi the woodcutter, I'll come with you. Together, we might be able to do it."

Garibaldi smiled. Sallina was a clever woman, and if he was going to escape the Duke, he would need someone clever to help him. "Okay," he said.

They shook hands.

"Can we say goodbye to our families?" Sallina said.

"I don't think so."

Sallina nodded. "No, I don't think so either. Which way, then?"

Garibaldi pointed along the top of the hill. "This way. If we run, we will reach the Deserted Forest by evening, and then we can continue towards the Sea."

And so it was that Sallina and Garibaldi began their great adventure.

The path Garibaldi and Sallina were walking along followed the top of a ridge. On their left the land sloped down to the river, and on their right, it sloped down to the Duke's estate. Neither of them wanted to meet anyone as they went along the path, so they watched the path ahead of them, to see if anyone was coming the other way. They looked down the slopes on either side, but they could not see far because the forest was thick with bushes and fallen trees.

Garibaldi looked back the way they had come. "I think we should try to run, if you don't mind."

"Why not ride your horse?" Sallina said.

"We could, but she would soon be tired, and I want to save her strength."

"What for?" Sallina said, "Don't we need to go as fast as we can, right now, so we can get away?"

Garibaldi did not answer right away.

"Well?" Sallina said.

Garibaldi stopped and patted Eliza on the neck. Her brown coat was warm and smooth. "I suppose you're right," he said, and he looked at Sallina. "Okay, let's ride her."

Garibaldi pulled himself up into Eliza's saddle and offered his hand to Sallina. She took his hand and grabbed the back of the saddle. She looked for something to put her foot in so she could step up behind Garibaldi.

"Where are your stirrups?"

"I don't use them," Garibaldi said.

Sallina frowned. He didn't use stirrups? How strange. She jumped. Garibaldi raised her firmly with his strong arms and she found herself sitting in the saddle behind him. Her chest was pressed up against him, and her legs were on either side of Eliza's tummy. She put her hands on the back of the saddle and lifted herself up off the lumpy leather.

"Are you comfortable?" Garibaldi said. Sallina was wiggling around behind him.

"The back of the saddle is sticking into my bottom."

Garibaldi moved forward as far as he could. "How's that?"

Sallina sat down into the saddle and slid forwards. Now she was really squashed up against Garibaldi. She put her arms around his tummy so she could hold on, and rested her head against his neck.

"That's fine," she said, and smiled.

Garibaldi shook his head and squeezed Eliza's sides with his heels. She started to trot, and they went along as fast as child running. Eliza's back went bumping up and down. After a few minutes, Sallina said, "Can we canter? It will be more comfortable."

It may seem strange to those of you who have not ridden a horse, but going a little faster makes for a smoother ride. The horse starts moving its legs in a different way, and its back stops bumping up and down. So Garibaldi squeezed Eliza's sides again. She went faster, and a little faster still, and her stride changed. She cantered along the path, going as fast as an adult running. Her back stopped bouncing up and down.

"Thank you," Sallina said said.

Sallina sat comfortably in the saddle and watched the trees go by.

"Will she get tired soon?" she said.

Garibaldi looked back so Sallina could hear him answer. "She'll go for a few minutes."

The path they had been following turned off the top of the ridge. Garibaldi slowed Eliza to a stop. Garibaldi and Sallina knew that the path went down through the forest to the Duke's estate. They did not want to go that way. They wanted to follow the top of the ridge and enter the Deserted Forest. But there was no path for them to follow to the Deserted Forest. Eliza stood on the turn in the path and panted. Her big lungs filled and emptied underneath the two riders. Her breath came out of her nose in loud snorts.

"We must go into the forest. But we can't ride in there. The branches are too low," Garibaldi said, "I think we should lead Eliza and run."

"Okay," Sallina said. She slid off the saddle and dropped to the path beside the horse. Garibaldi did the same. He patted Eliza on the neck. Her coat was warm and damp. She looked at him through one of her big brown eyes.

"Good girl," he said.

Sallina looked back the way they had come, back towards her home. She thought of her mother and father, and her younger brother. When would she see them again? What was happening to her? What was she doing riding into the Deserted Forest with a chest full of gold and the woodcutter's son? She shook her head. "Money is the root of all evil."

Garibaldi was looking back down the path as well. His father would soon find out what had happened, and figure out what Garibaldi and Sallina had decided to do. For some reason Garibaldi was sure that his father would smile at the thought of his son going off with Sallina and a chest of gold. But Garibaldi would miss his father. Their days in the forest together were good days. There were tears in the corners of his eyes. He looked at Sallina, hoping that she had not seen them. She was crying herself, and wiping her nose on a blue handkerchief. She looked up at him. "Oh, Garibaldi, what is going to happen to us?"

Garibaldi watched a tear slide down the smooth skin of Sallina's cheek, and looked into her eyes. He did not know what to say. But as he looked into her eyes, his heart beat faster, and he felt that he did not care where they were, or where they were going. Sallina looked away and wiped her nose. Garibaldi wondered what he should say. What did she want him to say? What would his father say? He remembered sitting with his father the night before, at the dinner table. His mother was standing in front of the fireplace with one hand on her hip, and the other hand holding a wooden spoon. His father was smiling across the table at Garibaldi. His mother said, "You know they all wish they had a man like mine." His father looked at her. "What kind of man is that, my dear?" She pointed the spoon at him and said, "You know what I'm talking about."

What was his mother talking about? Garibaldi did not know.

"I don't know what's going to happen to us," Garibaldi said, "But we made our decision. We have to keep going, and we have to go as quickly as we can. So let's go."

Garibaldi started walking into the dark, quiet forest, leading Eliza by her reins. Sallina waved goodbye to the path that led back to her home, and followed him.

On and on they went, along the ridge, up and up, and then down and down again, pushing their way through the plants that grew beneath the trees, and leading Eliza around the pine trees with the lowest branches. They saw no-one. They heard nothing but the chirping of a bird here and there, and the rustling of small animals among the dried leaves on the forest floor.

"Is this the Deserted Forest?" Sallina said.

"No, we must cross a stream and a hay field first."

In a while, they came to the stream. Garibaldi took his socks and boots off, Sallina took her sandals off, and they waded across. Eliza followed on the end of her reins. They climbed a gentle slope. At the top of the slope there was a field with tall grass growing in it. There were several deer standing in the grass, but when they saw Garibaldi step out of the trees, they ran away. Their white tails bounced up and down as they went towards the forest on the other side of the field.

"Wait a second," Sallina said, "Lets stay back in the forest for a minute to see if anyone else is here."

They waited, but they saw no one.

"We should cross the grass as quickly as we can," she said, "Let's ride Eliza."

"No," Garibaldi said, "She might get her foot stuck in a rabbit hole, or twist it on a rock. The soil is rocky here. With us both on her back, she might fall over and break her leg."

Sallina looked at the grass and the rocks. "Well, let's run, then."

They ran.

By the time they reached the forest on the other side, they were hot and tired. Sallina stood in the shade of the trees and breathed deeply. She looked around her. She was standing beneath a huge tree with tiny, thin leaves. Many old leaves had fallen on the ground beneath the tree and turned brown. Nothing seemed to be able to live under the tree, with all those sharp, dead, little, brown leaves. She looked into the forest. There were many of the same type of tree. Nothing grew beneath them. She could see a long way under the trees.

"What spooky trees."

"They are yew trees," Garibaldi said, "and they often grow in graveyards."

Sallina shivered. "I suppose this must be the Deserted Forest."

"Yes, it is."

"Must we really go into it?"

"If we cross the forest, we will come to the sea, and there, we can take a boat to somewhere far enough away that the Duke won't find us."

Sallina took a deep breath. "Okay, let's go."

They walked into the forest. Soon they could not see the sun shining on the grass behind them. The trees stretched out in every direction, as far as they could see. Garibaldi stopped and looked at the ground. There was a large brown lump there with some flies sitting on it.

"There's a black bear nearby," he said.

"Is it dangerous?"

"Not unless it smells food, like cheese or ham. They love ham."

"Well we don't have to worry, then. We have no food." She frowned. "I left my shopping basket behind."

Garibaldi started walking. Liza stood still, her head held low, until Garibaldi pulled firmly on the reins.

"We will be hungry by the time we get to the sea," he said.

"I'm already hungry," Sallina said. She took a few quick steps and caught up with Garibaldi. "And thirsty, too."

They walked on into the forest. It was getting dark when they came across a stream. Garibaldi put a handful of water in his mouth. He sloshed it around for a while and swallowed. "It's okay to drink."

By scooping up water in her hands, Sallina drank until she was no longer thirsty.

"That's better," she said, "Now it's time for supper. Where are we going to sleep?"

"I don't know. Let's keep going for another half an hour and see if we can find a good place."

Soon after, they found what they thought was an animal trail. But when Garibaldi looked at it more closely, he saw shoe prints, and brush-marks on the dirt. "Someone has been this way today," he said. He pointed at the brush-marks. "He was out gathering wood. He dragged a branch along the path."

"I thought this forest was deserted."

"So did I."

"Shall we follow the footprints to his house?"

"I think we should," Garibaldi said, "If he drags firewood, he's probably a hermit or something. He may not want to see us, but he probably won't hurt us, and he won't know about our gold, or the Duke chasing us."

"And perhaps he has some food."

"I'm sure he will have some food. Let's take some money out of the chest right now. We can use it to pay for supper and a place to sleep."

They took four gold coins out of the chest, two for each of them, and followed the footprints. After a few hundred paces, they rounded the bottom of a steep hill and saw a clearing in the forest. In the middle of the clearing was a stone cottage. Outside the cottage were some vegetable patches, some young corn stalks, and a few chickens. Behind the house was a stream of clear water. Outside the front of the house was an old man sitting in a big wooden rocking chair, smoking a pipe. He looked at them and smiled.

Sallina and Garibaldi stood still.

"Do you think he is a sorcerer or something?" Sallina whispered.

"No, I think he's an old man who lives in the woods," Garibaldi said.

The old man said, "Greetings, strangers," and took a deep puff on his pipe. He blew the smoke out in a big, gray cloud.

"Good evening, sir," Sallina said, "We are traveling to the sea, and we were planning to sleep in the forest, but perhaps we could purchase some food from you, and a place to sleep under a roof for the night?"

The old man took another puff on his pipe and rocked on his chair. He looked first at Sallina and then at Garibaldi. He took his pipe out of his mouth. "Two young people going to the sea," he said, "And perhaps with other people chasing them. You must be frightened and hungry." He smiled. "Of course you can stay here. I will be glad of your company, and if you want to tell me your story, I will be glad to listen."

"You are very kind," Sallina said.

The old man went inside and came out again with some corn for Eliza. Garibaldi and Sallina took off Eliza's saddle, brushed her coat, gave her the corn and a bucket of water, and went inside. The old man was making supper. "Will you tell me your names?" he said.

"I am Sallina, and this is Garibaldi."

The old man looked up and nodded. "My name is Ephistra."

Ephistra made rabbit stew with onions and potatoes. After their long day, Garibaldi and Sallina thought the stew was delicious, and the three of them together ate all there was in the pot. Afterwards, the old man lit his pipe. They sat around the fire with a candle on the table to give them light.

"So," Ephistra said, and blew a puff of smoke into the air. The smoke curled around the candle, and drifted towards the ceiling. "Are you being followed? I ask because I would like to know. Some visitors I like, but others I do not. Angry fathers and mothers, or policemen, are the sort of visitors I don't like."

Sallina reached into her pocket and took out her two pieces of gold. She held them out to the old man. "Here, these are for you. Please take them."

The old man took the coins and held them close to the candle so he could see them better. He looked at both sides of each coin carefully. "Hmm. These are old. This is the face of Duke Bloggwater, who died over a hundred years ago." He put the coins in his pocket. "Thank you, young lady."

"You're welcome. Thank you for supper."

The old man nodded.

"We're not running off to get married," Garibaldi said.

"You don't plan to get married?"

"No, of course not," Sallina said.

"Why of course not? Don't you make a good pair?"

"That's not why we're running," Garibaldi said.

He and Sallina told the old man their story. When they were finished, Ephistra said. "I can see that you are both frightened, and you have told me your story because you wanted my advice. I am an old man, and you probably think I am wise. Perhaps I am. But I can tell you that in the future, you must keep that chest of gold of yours a secret. In the places you are going, there will be many people, perfectly nice-looking people, who would kill you to take that gold away, if there really is as much of it as you say."

"There is," Garibaldi said.

"You probably want to know if I think you did the right thing. Do you?"

Sallina and Garibaldi nodded.

"I don't think you did."

Sallina let out a sigh, and Garibaldi looked down at the floor.

"You should have kept going to the Duke's house after your fight with the three ruffians. But the fight frightened you, and the words of their leader frightened you. So long as you brought the gold to the Duke, you would have done nothing wrong, so there would be no reason to throw you in jail, no matter whether the Duke believed the three ruffians or not."

"I knew it!" Sallina said.

"You knew it?" Garibaldi said, "You wanted to run as much as I did."

"Stop!" the old man said, "Stop, and listen."

Garibaldi and Sallina sat back in their chairs.

"You also wanted to keep the gold, and you had to think quickly. You decided to run with your treasure. Now that you have started to run, I don't think you should go back. If you go back, the Duke will know that you tried to run with the gold, and he will know that the reason you came back was because you decided the gold was not worth it. He may not want to punish you, but he will have to. He will have to show his people that they should not steal from him. A Duke must make his people frightened of him, or they will not obey. Believe me, I know."

"How do you know?" Sallina said.

"I'm not going to tell you my story. We are talking about your story. And I have more to say about it. You must go on. You should go west to Godiva, and take a boat to some far-away place. You could try Troka or Belgorash on the other side of the sea, or you could go north to Plantinak."

"Plantinak," Sallina said. The name sounded exciting.

"Tonight, you must sleep in here with your chest of gold. I will sleep on my chair outside and watch for anyone coming after you. I doubt they will catch up with you today, but they will find you tomorrow. They will send their hounds after you."

Sallina frowned. Send the hounds after them? That sounded terrible.

That night, Sallina and Garibaldi lay upon two thin, straw mattresses on the floor of the cottage. They each had a blanket to cover them and they each wore all their clothes. Garibaldi did not even take off his boots. The chest of gold rested on the floor between them. Ephistra was outside, sitting on his rocking chair in the dark. Eliza was outside too, her reigns tied to a tree.

In the darkness, Sallina said, "How can we trust him?"

"I'm too tired to worry about it," Garibaldi said.

"Is he still outside? Or has he gone to get the police?"

"He's not going anywhere through the forest at night. I trust him. Why would he lie to us?"

"He wants the gold, too," Sallina said.

"I'm sure he does, but he can't have it, except for another two pieces that I'll give him tomorrow."

"What if he sneaks in here in the middle of the night and tries to kill us?"

"I'll wake up, I wake up very easily," Garibaldi said, "which is a pity, because otherwise I would be asleep right now, instead of being kept awake by you talking."

"Honestly, is that all you can think about? Sleep? Our lives could be in danger right now."

There she goes again, Garibaldi thought, making fun of him. But he was so tired, he did not care. He and his father had been chopping down trees since the sun came up, and now… now he did not care about anything but rest. Moments later, he was asleep, dreaming of his father teaching him to hold an axe.

Sallina tried to stay awake, but with the sound of Garibaldi's slow, steady breathing beside her, she found she could hardly keep her eyes open. How could he sleep at a time like this? But before long, she was asleep herself.

Sallina had been dreaming of sitting at the table in the kitchen of her own home, with her brother making a pancake for her at the stove, and her father sitting opposite her, cracking open the top of a soft-boiled egg with a spoon. "Ah, perfectly done, my son," her father said, in her dream, and Sallina smiled. It was good to be home. That was when she woke up. The first light of a new day shone through the cracks in the shutters of the old man's cottage. Her real life was not right at all. Something had gone wrong. She lay upon her straw mattress and tried to go back to sleep. Maybe she could go back to her dream and see her mother.

Garibaldi sat up on his own mattress. A beam of sunlight shone in his eyes. He looked down at Sallina and she looked up at him. Neither of them spoke. Sallina wanted to cry. "It's going to be okay," Garibaldi said.

Sallina nodded. Garibaldi stood up. He put his belt on and stretched his arms and legs.

A little while later, Garibaldi and Sallina stepped out of the old man's house. The sun was rising into the sky. There were a few clouds here and there, and mist rose off the prickly bushes beneath the trees. The old man's chair was outside the door, but they could not see the old man himself. Eliza was standing beside a tree, eating some grass that grew at the base of the steep hill.

"He went to tell the Duke," Sallina said.

Garibaldi looked around and frowned. They heard footsteps on the other side of the house. The old man came around the corner. When he saw them he smiled. He carried three eggs in his hands. "Good morning, my young visitors, I trust that you slept well."

"We did, thank you," Garibaldi said, "How about you? It was very kind of you to sit out here in the cold while we lay sleeping inside your own house."

"I often sleep outside. I made this chair for sleeping in." He rocked his big wooden chair with one hand. He held the three eggs in the other. "Let's have some breakfast. My chickens were kind enough to lay three eggs this morning. I'm for soft-boiled, what about you?"

"Yes please," Garibaldi said. Sallina nodded.

Ephistra lit a fire. He put more wood on than he needed to boil the water. He boiled it quickly. He made tea with the water when it was hot, and dropped the three eggs into what was left in the pot. Soon he had toast and eggs and tea and apples on the table. Sallina and Garibaldi thanked him. The three of them ate without speaking.

When they were finished, the Ephistra said, "You should hurry. The Duke's soldiers might be here soon."

"And you think we should go to Godiva?" Garibaldi said.

"Yes. It is not the closest town, but you can get there through the forest without anyone seeing you, and you can take a ship from there."

"How far is it?"

"Riding through the forest, if you know the right paths, it should take one day. You could be there tonight."

Garibaldi and Sallina agreed to go to Godiva. The old man told them how to get there by taking the old stone paths that ran back and forth across the forest, left over from long ago, when the forest was not a forest, but part of The Empire. Sallina wanted to draw a map, but Garibaldi said he could remember the directions in his head.

Sallina shrugged, "Okay, but I hope we don't get lost."

"Trust me," Garibaldi said, "I know my way around a forest."

The old man gave them a bag of flour and the two blankets they had slept under, in case they lost their way and had to spend the night in the forest. They could use the flour to make bread. He gave them two onions, six apples, and three potatoes as well. "Thank you," Garibaldi said, "How can we ever repay you?"

"You could give me some more of that gold of yours, young man, I'm not too proud to ask for it."

Sallina opened the chest and took out a small handful of coins, perhaps twenty of them, and gave them to the old man. "There you go, don't spend them all at once."

The old man laughed. "I won't, young lady, I won't, and good luck to you, go on now, don't wait any longer, you must be on your way."

Garibaldi mounted Eliza and helped Sallina up behind him. Sallina put her arms around his waist. The old man smiled.

"Some advice before you go," he said.

"Please let us hear it," Sallina said.

"Your only hope is to work together. Don't let your greed and your fear trick you into fighting with one another. And don't think that you have no greed or fear. We are all greedy, and we are all afraid."

"Wise words, Ephistra," Sallina said, "Thank you."

"Goodbye Ephistra," Garibaldi said. He squeezed Eliza with his legs and she set off at a trot into the forest. As they went along the path, the yew trees ended, and in their place there grew beech trees with smooth bark and shiny leaves. Sallina was glad. She liked beech trees.

Eliza was breathing hard when they found the first of the old stone roads the old man had told them about. They let Eliza slow to a walk. They followed the path to the west. For the rest of the morning, they took a turn here, a turn there, and crossed a river, all according to the instructions the old man had given them. They said very little to one another. The forest was quiet and calm. At lunch time, they stopped and ate a some apples and drank from a stream.

After lunch, they rode along a broad path, looking for a turning to the left

"What a nice man he was," Sallina said.

"Yes, he was a nice man," Garibaldi said, "but I don't think you had to give him a whole handful of our gold. If you keep going like that, we won't have any left before the week is finished."

"Oh, come on, he did so much for us, and there are at least a thousand pieces in that chest. In fact, we haven't even counted them yet. There might be ten thousand in there for all I know."

"There might, but I think you should ask me before you give away so much of the money that is at least half mine."

"At least half?" Sallina said, in a loud voice. "What do you mean at least half? Why should you get more than I?"

Garibaldi noticed that she said "more than I" instead of "more than me", and it sounded strange to him that she spoke like that, but he supposed she must be speaking in the proper way. What was the point in arguing with someone who was so clever with words, because that was what arguing was all about wasn't it? Being clever with words.

"Well?" Sallina said. She leaned around his shoulder to look him in the eye.

"Take all the gold if you want it," Garibaldi said, "I'm not going to argue with you."

"Oh, that's great! Don't think about what you said, just tell me to take all the money!" Sallina took her arms from around Garibaldi's waist and put them on her hips. She closed her eyes and took a deep breath. "I don't want to take all the money, all I want to know is why you think you should have more than half of the money."

Garibaldi did not answer. Anything he said would make him look stupid, so he should just be quiet, and Sallina would think he was more clever than he really was.

They rode on in silence. Garibaldi saw a turning on the left, and they took it. The turning put them on an overgrown stone road. Every one hundred steps or so there was a broken stone statue lying by the side. Sallina wanted to get off Eliza's back and look at one of the statues more closely, but she was too angry at Garibaldi to ask him to stop the horse, so she said nothing.

An hour later, the road ended at a large pit with a pond in the bottom. Eliza stopped at the edge. She put her head down and started chewing some grass.

"Well?" Sallina said.

"Ephistra said nothing about this pit," Garibaldi said.

"Perhaps it's new."

"No, it's at least a hundred years old. You can tell by the size of the trees growing out of the side of it."

"So what's going on?"

"Either he gave me the wrong directions, or I have forgotten the directions, or we missed a turning while we were arguing."

"Let's go back, then, and find the turning."

They went back. When they found another turning, they took that one instead. Half-way through the afternoon, they decided that this turning must be wrong as well, because it was not taking them in the right direction.

"Now what?" Sallina said.

"I don't know," Garibaldi said.

"If we go back, and the police are coming after us, we may bump into them."

"True."

They sat on Eliza's back while she drank from a little puddle in a hollow stone by the road.

"We could leave the paths and go through the forest and try to find the correct road," Garibaldi said, "and then go towards Godiva."

"Okay, let's do that. Do you know which direction to go?"

"Yes," Garibaldi said.

"Are you sure?"

Garibaldi frowned. Why did she ask the same question twice?

"What do you want me to say? Yes or no?"

"I want you to tell me if you are absolutely sure that you know the way."

"No, I'm not absolutely sure."

"Thank you."

"Now what do we do?" Garibaldi said.

"We do what you said we should do, try to find the right road."

Garibaldi frowned and stared at Eliza's neck. He shook his head.

They tried to find the right path, and perhaps they would have found it if it had not started to rain. It was not the rain that made it difficult for them to find their way, it was the clouds. Garibaldi could tell which way they should go so long as he could see the sun through the trees. When the clouds hid the sun, he tried looking at moss on the tree trunks instead. In his experience, most tree trunks had more moss growing on one side than the other, and the side with less moss was the side the sun shone on the most, which was usually the south side. But in the Deserted Forest, the moss seemed to grow all around the tree trunks, or on different sides from one tree to the next.

Towards the end of the afternoon, they found another one of the ancient stone roads. They followed it in the direction Garibaldi thought was west. The rain was still falling. It soaked their hair and their clothes. Even though it was summer, and the rain was warm, they were cold sitting on Eliza's back. They wrapped the blankets Ephistra had given them around their shoulders. The road brought them to a clearing. In the middle of the clearing was a ruined stone cottage. The roof had fallen down in most places, and one of the walls had fallen over. To their left was a hill that rose steeply. The top of the hill was rocky and bare.

The road continued on the other side of the clearing.

"We might see Godiva from the top of that hill," Garibaldi said.

"Let's go up and look before it gets dark," Sallina said.

"It's too steep for Eliza to climb."

"So go up on your own. I'll wait here."

Garibaldi did not say anything.

"What are you waiting for? Are you too tired to climb the hill? Do you want me to climb it for you?"

"I'm not too tired."

"What is it, then?"

Garibaldi stared at Eliza's neck for a while. Sallina waited.

"I think you might want me to leave you alone with my horse and the gold so that you can ride off and leave me."

Sallina got down off Eliza's back and stood on the ground. She looked up at Garibaldi.

"Didn't you listen to what the old man said? About greed and fear?"

"I'm not afraid. I'm not greedy."

Sallina shook her head. "Well, I'm not climbing the hill on my own either. If you don't trust me, why should I trust you?"

Garibaldi slid off Eliza's back and stood beside her. "It's raining and it's getting dark. Let's stop here for the night." He pointed to the ruined cottage. "We can make a fire under what's left of that roof and get some sleep. We can decide what to do in the morning."

Sallina nodded. "Okay." She was hungry and wanted to make some bread.

They tied Eliza up under the cover of a big oak tree. They brought her water from a stream nearby. Garibaldi gathered dead wood from the forest. There was still some dry wood under the largest trees. He lit a fire with the matches he kept in Eliza's saddle bags. Sallina made bread in the fire by putting a heavy lump of dough in the coals. There were not many things Sallina knew how to cook, but camp-fire bread was one of them. After supper, they sat leaning close to the fire with their blankets wrapped around them. The rain was still falling, but the roof kept most of it off them. They sat without speaking. The only sound was the rain pattering upon the forest and the crackle of burning wood. The sun went down and it was dark.

"Did you forget the directions?" Sallina said.

Garibaldi put two more sticks on the fire. "I don't think I did" He spoke the directions out loud again, and they seemed to be exactly as the old man had spoken them.

"I think you remembered." Sallina said. She stared into the warm light of the fire. "We became lost because we argued."

"Maybe," Garibaldi said.

He lay down beside the fire. Sallina did the same. "Sleep tight, Garibaldi."

"You too."

They woke up in the middle of the night, shivering with cold. The fire had gone out. It was still raining and it was absolutely dark. Garibaldi lit a match and looked at the fire. A puddle of water had formed upon the ground and all the coals were wet. The match went out.

"The ground at the bottom of the wall is dry," Sallina said.

They lay along the bottom of the wall. The ground was dry, but it was hard and cold. The stone wall was cold too, and their blankets were thin and wet. Garibaldi wanted to say that if they lay close together and shared the blankets, they would have two bodies and two blankets to keep them warm, and that way they might be able to sleep. But he didn't say anything. If it had been colder, he would have said something. But they were not so cold that they were going to be hurt. He started hoping that Sallina would say the same thing instead of him. She was a clever woman, why didn't she suggest that they lie close together? Perhaps she did not want to lie next to him. Or perhaps she was nervous about asking him for the same reasons that he was nervous about asking her. Never mind. It was not worth worrying about. They would be tired in the morning, but they were young and strong. They would still be able to ride to Godiva.

The rain stopped just before the sun came up, but the clouds remained. When the first light of day entered the valley, Garibaldi pushed his blanket aside and rose to his feet. Sallina sat up and leaned against the wall. Garibaldi stretched his legs and arms. He walked out from under the roof and jumped up and down to warm himself up. When he came back under the roof, he knelt next to the remains of the fire. It was wet and cold. "I should have saved some dry wood from the fire last night."

"Don't worry about it," Sallina said, "We'll be in Godiva by nightfall. I have the answer to the problem of climbing the hill."

"What's that?"

"We put the gold in a bag and carry it up to the top of the hill together. We leave Eliza here at the bottom. We look around at the top, and then come down and go."

Garibaldi nodded. "I like it."

They took the saddle bag with the chest of gold off Eliza's back. Garibaldi carried his axe in one hand. He slung the bag over his shoulder with the other. The hill was higher than they guessed, and difficult to climb. They helped one another up the steepest parts, and stopped to rest a few times. When they reached the top, they looked down into the valley where they had spent the night. There was the ruined house. There was Eliza under the oak tree. There was the ancient stone road winding up the valley and out the other side of the clearing.

Sallina looked up at the sky. She could see the yellow disk of the sun through the clouds to their right, in the direction they had come from. She pointed to it. "That must be east." She turned her back to the sun and pointed the other way. "So that must be west."

"Yes," Garibaldi said.

In the distance, beyond several hills and valleys, they saw smoke rising from a town. On the other side of the town, something flat and gray stretched on into the farthest distance beneath the clouds.

"The sea," Sallina said, "We are not as far from it as I thought."

They looked at one another and smiled. A noise came up the valley. It was a clomping and clattering noise. Both of them knew what it was, and they stopped smiling. It was the sound of horses on the road. They dropped to the ground and lay on their bellies behind a bush. They stared through the bush down into valley. They heard another sound, one they liked even less than the sound of horses. They heard dogs barking.

Four dogs came running into the clearing. Eliza let out a whinny and reared on her hind legs. The dogs went in four different directions, sniffing the ground. Three soldiers rode into view on large horses. They carried swords at their belts, spears in their hands, and crossbows on the backs of their saddles. They wore chain mail shirts. Behind the soldiers rode another man. He was not wearing armor, but he carried a long-bow. Sallina and Garibaldi had never spoken to any of these men, but they recognized them all. Three of them were the Duke's soldiers, and the last one was one of the Duke's rangers.

The soldiers dismounted. They searched the cottage and the space around it. The Duke's ranger jumped off his horse and looked at the ground at the base of the hill, where two of the dogs were sniffing and barking.

"They have found our trail up here," Sallina said.

"Yes, we have to run," Garibaldi said.

"But what about Eliza?"

"We have to say goodbye to Eliza. She'll be okay. I'm glad we came up together, and with the gold, too. That was smart of you."

"Where do we go?"

"Down the other side of the hill."

They ran down through the trees on the other side of the hill and into another valley. They ran up the other side of the valley to the top of a ridge. The chest of gold banged against Garibaldi's back. At the top of the ridge, he stopped and waited for Sallina to catch up with him.

"I have to rest," he said, "The chest is hurting me."

"I'll carry it," Sallina said.

Garibaldi looked at her.

"Garibaldi," Sallina said, "Why do you suspect me? You're carrying your axe as well. Let me carry the gold."

"I don't want the chest to hurt your back."

"Really? Or are you worried I'm going to run off into the forest with the gold and leave you? And if you are, how do you think I could run faster than you if I was carrying the gold?"

Garibaldi looked down at the ground. Is that what he was thinking, that she would steal the gold? It seemed to him that he was just worried about her getting tired and hurt. But perhaps she was right. Perhaps he did not know what he was thinking. He gave the bag to Sallina.

They started running again. Soon, Sallina's back began to hurt too. With every step she took, the bag flew up and bumped her. The heavy weight of the gold pushed the hard edge of the chest into her skin. After half an hour, she stopped.

Garibaldi took the bag from her and looked inside. "The chest has sharp corners. Let's pour the gold out of it into the bag and throw it away."

Sallina nodded. She was breathing so hard she did not want to speak. Garibaldi poured the gold into the bag and threw the old chest as far as he could into the forest. He did not want the soldiers to find it. He looked at Sallina. "Are you ready?"

Sallina nodded. They started running. On and on through the forest they ran. They heard no sound of the soldiers and dogs. They came to a stream that was too wide to jump across. They stopped and looked at the cold, noisy water. Garibaldi pointed down the hill. "Let's wade in the water, down the stream, for a hundred meters, and get out on the other side. That will make it difficult for the hounds to follow us."

"They will be expecting us to go down the stream," Sallina said, "Because that's the way they know we want to go. What if we go up the stream, then off in a strange direction, and then go west. Will that be better?"

Garibaldi nodded. "Good idea."

They waded in the center of the stream, up against the current. When they came to a gravel bank, they jumped out and ran into the trees. At mid-day, they found a blackberry bush. Its blackberries were sweet and large. They stopped and ate as many as they could. They drank water from a spring. The spring water came up out of the ground in a pool.

"Such delicious water," Sallina said.

Garibaldi nodded. He picked up the bag that held the gold. "Have you drunk enough?"

"Yes."

"We must keep running."

Sallina stood up. "Okay, let's go."

They ran through the trees. Sallina followed Garibaldi. He seemed to know where he was going. She was lost completely in this forest, with no idea which direction was which. It began to rain. Big drops of water fell from the branches of the trees. She watched the ground in front of her. She was wearing only sandals. She did not want to trip up, or cut her foot.

Garibaldi was a strong young man, and he could run a long way. But he did not think Sallina could run far. As he ran through the forest, with Sallina behind him, he was trying to decide what they would do if Sallina became too tired to run any farther, or if her feet became too sore. He was worrying about how they were going to get away if they had to stop. But time went by, and Sallina kept running. When they looked out across the forest from the top of a hill, Sallina seemed exhausted, but she did not complain. Her dress was torn in several places, and dirty all over. Her hair was wet with sweat and her face was red. She had been carrying the bag of gold.

"Thank you," Garibaldi said, "It's my turn to carry it."

He took the bag from Sallina's back. She stood up straight and stretched. She winced. Garibaldi shook his head. "I'll carry it from now on."

Sallina did not argue with him. Garibaldi looked down the hill. The fields of Godiva were below them. The light of the sun shone through the clouds ahead of them. "It's not far now, anyway," he said.

"How much daylight do we have left?" Sallina said.

"An hour or two." He looked at her. "Can you start now?"

"Yes, let's go."

The last half hour of walking through the forest was hard. The forest was thick and it was dark beneath the trees. Garibaldi had a scratch on his face from a thorn bush. Sallina stubbed her toes many times on tree roots. They pushed their way through spider webs and hanging vines. But as they approached the first houses of Godiva, they agreed that it was a good thing that they arrived just after the sun went down. They were both so dirty, wet, scratched, and tired that if it had been bright daylight, people would have stared at them and asked themselves, "What are these two young people running from? What were they doing in the Deserted Forest?" The town police might have stopped them and asked them questions, questions such as "What do you have in that bag, young man? Why are you carrying that axe?" As it was, nobody paid any attention to Sallina and Garibaldi as they walked along Godiva's main street to the Dalmatian Hotel and went through the front door.

Once inside, they nearly bumped into a big, tall, man with a chest that stuck out and arms that were even larger than Garibaldi's. He was wearing a cooking apron.

"Well, well," he said, "two young lovebirds run away?"

Sallina was about to say something like, "We are not young lovebirds," but she decided against it. Instead, she looked up at the man's face to see if she could tell what sort of person he was. He smiled at her and at Garibaldi. He was the innkeeper. He looked Sallina straight in the eyes and waited for her to speak. Sallina reached into the bag that Garibaldi carried and took out five coins.

"Here's five gold pieces for a good room," Sallina said, "with hot water, a good supper, a change of clothes for me, and your respectful silence upon the matter of our presence here."

The innkeeper took her coins. "Rest assured, my dear lady," the innkeeper said, "our discretion we provide at no charge to all our guests, but your money will pay for the best of the other items you desire. Come this way. You can sign the guest book in the morning. Here, follow me, up the stairs. I see you travel light. Well, we will provide you with all you need. Including a nice soft bed." He turned and winked at them.

At the top of the stairs, he opened the door to a room and stepped aside to let them through. Sallina and Garibaldi walked in. The room was large and clean. It had its own fireplace. There was one bed against the wall with a thick, down-filled comforter on top. The bed was big enough for two people to sleep in side by side. The innkeeper stood in the doorway. "My wife will be up to measure you for clothes and bring you hot water."

Sallina turned to face him. "Thank you."

"I remember when my wife and I were young," the innkeeper said. "My wife's father said to her, 'That boy will never amount to anything'." The innkeeper laughed, and put his hand upon his belly. "Meaning me. We ran away from our village and came here to the big city. We've lived here happily ever after. Raised two children. Bought this inn." He sighed and looked at the ceiling. "So you came to the right place."

He winked again and closed the door, leaving Garibaldi and Sallina alone in the room. They looked at one another. Garibaldi raised one eyebrow. Sallina shrugged her shoulders. She walked to the window and looked out. It was dark. There was an alley below the window. She closed the thick curtains and turned to Garibaldi. "We made it."

Garibaldi nodded. He looked at Sallina's face. She smiled at him. They both looked at the bed.

"My gosh," Garibaldi said, "That looks comfortable."

"It does. Comfortable and warm," Sallina said, "I was cold last night. Tonight I want you to make sure I'm warm."

"How am I going to that?" Garibaldi said. "By keeping the fire going all night?" He looked at the fireplace. There was some wood next to it. But not enough to keep the fire going all night.

"No," Sallina said, "By holding me."

Garibaldi looked at her. "Oh," he said. "Okay."

Sallina smiled. "But I'll let you have your supper first."

Garibaldi sat up in bed. Sunlight shone around the edges of the curtains. He and Sallina had kept one another company until late the night before. He was tired, but he did not mind.

"It's late," he said.

Sallina looked up at him. "I know."

He lay down. The bag of gold was in the bed between them. Sallina pushed it up underneath the pillows and moved close to him. "I knew it was a good idea running away with you."

Garibaldi smiled. Even with the Duke's soldiers chasing them, and their family left far behind, he felt happier and more excited to be alive than he could remember. He kissed Sallina on the nose.

Sallina raised herself on one elbow. "I don't think the soldiers followed us into the forest at all."

"You don't?"

"No, I don't. Their horses would not be able to follow us up the hill. The soldiers would have to dismount and go on foot. They would not be able to run as fast as us with their chain mail shirts on, and carrying their swords and spears. Only the man with the bow would be able to follow us, and I think he would be scared to do so, because you still have your axe."

"Ha!" Garibaldi said.

"Well, you scared off those three young men back home."

"They were cowards," Garibaldi said.

"Either way," Sallina said, "I don't think the man with the bow would follow us on his own."

"So what did they do, go home?"

"No, I think they would guess that we were coming here to Godiva, and they would turn around and ride here by the roads as quickly as they could."

Garibaldi lay on his back looking up at the ceiling. It seemed to him that she must be right, and if she was, the soldiers could reach Godiva at any time. They might be in the town already.

"When did you figure this out?" Garibaldi said.

"When I woke up."

"Why didn't you say anything?"

Sallina tilted her head and smiled. "I was watching you sleep."

Garibaldi pulled the comforter off his body and stepped out of bed. There was a pitcher of water on a table, with a bowl next to it. He poured water into the bowl and washed his face. He dried himself with a white towel and began to pull on his dirty clothes. "I think we should get out of here."

"I suppose you're right," Sallina said. She got out of bed. The air of the room was cold against her skin. She pulled on the underpants, blue trousers and white shirt the innkeeper's wife had brought her the evening before. She wondered when she and Garibaldi would get a chance to share such a comfortable bed again. She picked up her sandals. "My sandals are wearing out"

Garibaldi crossed the room and looked at the sandals while he tightened his belt. "Perhaps we can buy some shoes for you before we get a ride on a ship."

"If we have time," Sallina said. She tied the sandals to her feet. "I'll go downstairs and ask the innkeeper to bring us some breakfast."

"Good idea," Garibaldi said.

Sallina unlocked the door, opened it, and stepped into the corridor. "Back in a minute." She closed the door behind her.

Garibaldi looked around the room. Sallina's old skirt and shirt were lying on the floor. They would be fine after some washing and stitching. He picked them up and put them in the saddle bag with the gold. He made sure the clothes wrapped around the gold so that the bag would be softer when he carried it. He opened the curtains and looked out the window. The clouds of the day before had cleared.

Sallina opened the door. "They're here!" She closed the door behind her and locked it.

"Who?"

"The soldiers! They're downstairs, talking to the innkeeper. I heard them as I came down. They were asking him if we were staying here."

Garibaldi picked up his axe. Sallina ran to the window and opened it. Below the window was the roof of another part of the inn. "Quick, out here." She climbed out of the window and onto the roof below. Garibaldi passed her the bag of gold and his axe, and climbed out himself. They stood on the roof, trying to decide how to get down. Behind them, through the window, they heard a man shouting from the other side of the door of their room.

"Open up," he said, "In the name of Duke Marcus!"

Garibaldi looked down at the alley below. "Can you jump that far down?"

Sallina sat down on the edge of the roof, pushed herself off, and dropped to the alley. She fell as she landed, but she stood up right away. She held her hands up for the bag. Garibaldi dropped it to her. The back was so heavy that she could not catch it. It landed on the ground with a crunch. She picked it up as quickly as she could.

Garibaldi sat on the edge of the roof, holding his axe in one hand. There was a crash from the room behind them. The soldiers had broken down the door. Garibaldi dropped to the alley and landed on his feet. He took the bag of gold from Sallina.

"Let's go," she said.

"Which way?" he said.

Sallina looked up and down the alley. Above them, they heard the soldiers shouting. One of them said, "Get out there!"

"They're climbing out the window," Garibaldi said.

Two men in blue coats came around the corner. There was a crowd of ten or twenty people behind them. Sallina guessed that the men in blue coats were policemen.

"There they are!" the policemen said.

The policemen ran forwards. The crowd followed close behind. Sallina ran down the alley away from the policemen. Garibaldi followed her. She looked back over her shoulder. The policemen were not fast runners. Some of the people were getting ahead of them. The alley was narrow. The crowd were pressed tight between it's walls.

"Throw some of the gold!" Sallina said.

"What?"

"Throw some of the gold, it will slow them down."

Garibaldi reached into the bag and took a handful of coins from among Sallina's dirty clothes. He threw them over his shoulder. When the gold landed in the alley, the people ran past the policemen and kneeled down to pick up the coins. Garibaldi threw another handful.

"Stop!" the policemen said to the people picking up the coins. "That gold does not belong to you."

Sallina and Garibaldi kept running. Sallina turned one corner and another. They ran out from between two large buildings next to the sea. There were walk-ways built out over the water, held up by wooden posts. Five ships and many boats were tied up next to the walk-ways. Sailors were walking onto the nearest ship along a plank of wood, carrying sacks over their shoulders.

Sallina and Garibaldi stood in the middle of the street that ran along the edge of the water, breathing deeply. "The docks," she said.

"Shall we try to get a ship?" Garibaldi said.

"We don't have time. They will find us soon."

"What else can we do?"

Sallina bit her lip. She was thinking. Garibaldi tried to think too, but all he could do was look back the way they had come and watch for the policemen. He held his axe firmly in one hand and the bag of gold in the other. Should he fight with the police? No, he did not want to hurt anyone.

"If we walk down one of the docks," Sallina said, "and the soldiers catch up with us, we will be trapped."

Sallina looked at the ship in front of them. It must be leaving soon because the sailors were loading it with sacks and boxes. The name of the ship was painted on its front side in large red letters: the Reliant. Nearby, a fat man in a silk jacket and fine wool trousers was talking to three sailors. The sailors stood next to a wooden crate on the dock. The crate was so large that it came up to the fat man's tummy.

"How are we going to lift this here crate onto the ship without a crane, Captain?" one of the sailors said.

"It's full of silk, my lad, light as a feather," the fat man said. He lifted up the lid of the box. "See for yourself."

The sailors looked in the crate until the fat man lowered the lid. "Run and get hammers and nails, and make this lid fast. I don't want it coming off on the way. This silk is going to make us a tidy profit."

"Aye, aye, Captain," the sailors said. They turned and set off towards the Reliant, leaving the Captain behind.

The fat man patted the crate once and began to cross the street. When he saw Sallina and Garibaldi he slowed down. He stared at Sallina. He stopped. Sallina smiled at him. Why was he looking at her? She tried not to breath so hard. The fat man smiled. He touched his hat. "Good day to you," he said. He continued across the street.

"Good day, Captain," Sallina said.

The fat man walked into nearest of the large buildings. Sallina looked at the crate. Everyone around them was busy. No one was looking. "Quick. They'll nail it shut, but you can cut your way out with your axe, let's get in the crate."

"What?" Garibaldi said.

Sallina walked towards the crate. She looked around to see if anyone was watching. Garibaldi followed her.

"You're crazy," he said, "We won't have enough air to breath. What are we going to eat?"

They stood by the crate.

"Quickly," Sallina said. She slid the lid over, so that a corner of the box was open. She looked around one more time, and climbed in. Garibaldi crouched and looked up and down the dock. Even though there were so many people around, nobody was paying any attention to them.

"Come on!" Sallina said from inside the box. "Hurry!"

Garibaldi put his axe and the bag of gold in the crate and climbed in. As soon as he was inside, Sallina slid the lid back into place so that it covered them up. Inside the crate, it was too dark to see at first, but some light came in through cracks in the lid and sides. After a while, they could see well enough. They were pressed up against one another, lying upon rolls of cloth.

"Let's get down under the silk so they won't see us if they lift the lid," Sallina said.

They moved the rolls up from under them and laid them on top. When they were satisfied that no sailor would see them if they opened the crate and looked inside, they both lay there panting, with the weight of the silk pressing upon their tummies, and their faces close together.

"Sallina," Garibaldi said, "This is crazy. We'll be trapped in here. I don't like small spaces."

"Do you have a better idea?"

"No," he said, "I don't."

"We can get out any time with your axe."

"Unless they put a dozen sacks of grain on top of the lid," Garibaldi said.

They heard the sailors coming back to the crate. They tried to breath quietly so that the sailors would not hear them. They were worried that the sailors would open the crate and check the silk, but as it happened, the sailors did not lift the lid at all. They moved it over, so it was in just the right place, and went to work hammering nails through the lid around the edges. In no time at all, the sailors were finished, the lid was nailed in place, with Garibaldi and Sallina inside.

The sailors walked away. Sallina and Garibaldi heard the many people running and shouting. The soldiers, the policemen, and the crowd had reached the docks.

"Where are they?" one of the soldiers said, "Has anyone seen a young man and a young woman?"

A sailor laughed. "Oh yes, I've seen a few young women, and far too many young men."

"This is serious, they're thieves."

"I ain't seen nothing, sir knight, I swears it."

The crowd moved away along the street.

"Phew," Sallina said.

Garibaldi and Sallina pulled the rolls of silk off them until they were lying on top again, which was much more comfortable. There was enough space on top of the silk for them to lie on their sides and face one another.

The sailors returned to the crate. They tried to pick it up, but put it down again. "I say, I thought the Captain said the crate was light as a feather."

"Come on, lads, try harder," another sailor said, "All together now."

They lifted the crate. Garibaldi and Sallina felt themselves being carried down the dock. When they reached the plank that led up on to the ship, the sailors put the crate down and talked for some time about how they were going to get the crate up the plank and onto the ship. They did not want to take the time to borrow a crane to do the job. The Captain had told them to get the crate on the ship quickly, and the crane would take an hour to set up. But the plank between the dock and the ship was too narrow for all the sailors carrying the crate to walk up at the same time. In the end, the sailors put a second plank next to the first, and walked up along both planks at the same time, with the crate between them. As they carried the crate up the planks, they breathed hard and shouted to one another.

"Harry, you idiot, mind your foot!"

"I'm minding my foot. You mind your tongue. And watch your end of the crate. You're holding it too low!"

"I'm too old for this, I am."

"This here's some special silk, it is, it's made by silk worms that eat rocks."

Sallina and Garibaldi heard the voice of the fat man. "What's all the fuss about, gentlemen?"

"This here crate is heavy enough to sink a sloop, Captain."

"Nonsense," the Captain said, "You're all getting fat and lazy from a week of lounging around. It's time we were out to sea again. Put your backs into it."

"You're a fine one to talk, Captain."

"Watch your mouth, Harry, or you'll be scrubbing the deck tomorrow."

"I'm not afraid of hard work, Captain."

"I see," the Captain said, "So the grumbling is just a way of passing the time, is it?

Harry grunted and the crate shook. "Would you rather I sang, sir?"

"You can wail like a siren for all I care, just get the crate on the deck and lash it before the tide turns."

And so the sailors carried the crate up to the top of the planks and onto the deck of the ship.

"Where do you want it, Captain?" Harry said.

"Tie it down right there and cover it with sail cloth. I want it wrapped double in the hold, but we're supposed to be off this pier in an hour, so leave it there for now."

The inside of the crate went dark. Garibaldi groaned.

"Are you okay?" Sallina said.

"I don't like small spaces. It's always, always a bad idea to get into a box and have someone close it on you. It's a very bad idea. Nobody should ever get into a box like this."

"Don't worry," Sallina said. "We knew before we got in that we could get out, because we have your axe."

"I can't swing the axe in here, there's not enough space. I might chop your arm off."

Sallina frowned. He was right. How could he swing his axe in here? Well, at least they had escaped from the police. "I'm sure you could make a hole with your axe in this crate anyway, given enough time."

The sailors carried things onto the ship for another hour. Sallina and Garibaldi listened to them shouting at one another. Sometimes the things the sailors said to one another made Sallina and Garibaldi giggle. The sailors laughed too, and complained, and argued with their captain. But mostly they laughed.

Eventually, the sailors all came aboard, pulled up the planks, and untied the ship from the dock. Sallina and Garibaldi heard sailors calling down from above them.

"They're climbing on those tall wooden poles that hold up the sails," Garibaldi said.

"The masts," Sallina said.

"Look lively on the main mast, Sharpy!" Harry said. "Unfurl the main-sail!"

The ship began to move. It rocked slowly. They heard the sounds of the docks growing quieter as the Reliant slid out of the harbor and left the town behind. After a while, Garibaldi started to think that they were quite safe in the crate. They made themselves more comfortable by moving some of the rolls of silk into better places. They were both tired. Before long, they were fast asleep.

Garibaldi woke up. It was dark. He was lying upon rolls of cloth. The ship was rocking.

"Sallina," he said.

Sallina moved closer to him and whispered in his ear. "Well, here we are, all alone in a crate of silk."

"Yes, we are."