Text © 2003-2024 Kevan Hashemi

This book combines sixteen episodes published sequentially in The Adventurer's Gazette. We reproduce them here with the permission of the Adventurer's Gazette, subject to the condition that they not be altered in any way. Consequently, we reproduce the advertisements carried by the original magazine printing. When I first wrote this account, I decided to change the names of nearly all its characters and places, so as to protect their privacy. In order to make it obvious to the reader which names I had changed, I decided to use replacement names that were obviously absurd. Since then, however, some readers have complained that my absurd names are insulting, or even offensive. I would like to change the names so as to avoid giving offence, but, as I have said, we are not at liberty to change the text. Therefore, to those of you who are offended by my absurd names, all I can do is apologize, and assure you of my innocent intentions.

Gristel Virage, 6 October 2479

Brought to you by Jafar's Fish and Crustacea. We bring our seafood in by destrier and hippogriff, packed in ice all the way. Some of it might be expensive, but we have something for every budget. Our hours are 5 am to 10 am every day but Wednesday. Visit us at 23 Kurdestan Boulevard in downtown Pakesh.

My husband and I stood before our eleven-year-old daughter, Romayne. We had just returned home from a three-hour meeting with our agent.

"What's the matter?" Romayne said.

"It looks like we have our next job lined up," I said.

"Oh."

We stood in the living room of our house.

"Let's sit down outside and talk about it."

"I need something to drink," Quayam said, and went into the kitchen.

Romayne and I walked out onto the veranda. It was warm and sunny outside. We pulled three chairs up to the table and sat down. Romayne stared at me. I looked out at the garden. A sparrow was playing in our birdbath. In our city, leaving water out for the birds is a luxury. We live in Pakesh, on the north side of the Ursian Desert.

"What job?"

"We're not sure we're going yet."

"You will."

I closed my eyes. When I opened them again, she was still staring at me.

"How long will it be this time?"

"A year."

"What!"

Quayam walked out with a tray carrying three glasses and a pitcher of iced water.

"How can you do this to me?" Romayne said.

"Do what?" Quayam said.

"Go away for a year," I said.

Quayam put down the tray. "Somebody has to go."

"Why? We don't need more money."

"This isn't about money," Quayam said.

There were tears in Romayne's eyes, and she put her head in her hands.

"Have some water," Quayam said.

He poured a glass for each of us, sat down, and took a long drink himself. "Ah. That's better."

Romayne stared at the table.

"You remember Richard Crockford," I said.

She nodded.

"He did card tricks for you," Quayam said.

"I know."

"He went to Feras," I said.

She looked up. "What! You're going to another universe?"

"Another planet."

"That's what I meant."

"We're not certain we're going," Quayam said.

"That's what you always say. You're going to another planet, and you'll get lost for years."

I laughed.

"Don't laugh at me!"

"You just read that book, Hossein of Susa, and he gets lost."

"So what?"

"Hossein of Susa," Quayam said, "is a fictional character."

"I know he's fiction."

"We're professionals. We don't miss conjunctions, and we don't get lost."

She put her head in her hands. Quayam put his hand on her shoulder. "I guarantee it."

"Richard is being held by a king," I said, "or warlord, I don't know what his title is exactly, but he has his own palace, and he's keeping Richard in it."

"Poor Richard."

"Richard's friends escaped, but they were caught. The warlord had them beheaded and made Richard watch."

"Yuck."

"Quite," I said. I took a drink.

Quayam said, "We're thinking of going and rescuing him."

"Why wouldn't you?" Romayne said.

"Why would we?" I said.

"We're talking with Careem," Quayam said, "and with Richard's secretary."

Careem is our agent.

"If you're going, why don't you just say so, instead of making it look as if you don't want to go, and then going anyway."

"We don't want to be away for a year," I said.

"Well don't, then."

"We think we have to. Richard is our friend."

"Then go."

Painful though the conversation was, it was going better than last time, when Romayne threw a plate at me. I looked out at the garden. Now there were two birds playing in the bath.

"You shouldn't waste water like that," Romayne said, "There are people in the city who can't afford to buy enough water to drink."

This is not true, so far as I know, but I chose not to disagree with her.

"So?" Quayam said.

"It's not nice that they are thirsty and we put water out for the stupid birds."

"Being stupid doesn't mean you have to go thirsty."

"I'm serious, Dad."

"So reach into your own pocket," I said, "and buy some water for the poor people, why don't you?"

"I'll match every liter," Quayam said, "twice over. That's three liters to the poor for the price of one."

"You should do ten to one."

I looked at Quayam. He was smiling.

"Okay," I said, "this is getting off the point."

"When you're gone. I'm not going to let Mary put water out for the birds."

"We'll keep that in mind," I said.

"So when are you going?"

"If what Richard Crockford's secretary says is true," Quayam said, "We'll go in a couple of weeks."

"What does she say?"

"He," I said.

"His name is Nicholas," Quayam said, "He sailed from Endromis to meet us."

"What does he say?"

"He says the trip will take a year," I said.

"And what if it takes longer?"

"We won't go."

"How will you know until you get there?"

"We'll get there by conjunction, and come back by conjunction. The conjunctions are reliable. They occur for the same length of time at the same intervals. No matter what happens, we'll get our conjunction home."

"So you are going, then."

You might be thinking that it was a mistake to bring the matter of our trip up with Romayne before we were certain of it, but our experience has been that, practically speaking, we cannot hide such things from her anyway.

"I suppose Thristen is going too," she said.

Thristen is our partner.

"If we go, he'll come too. We'll need him."

Romayne sipped her water. "Why? Are you going to kill a lot of people?"

"Oh come on!" I said.

"There is no summoning medical aid from the gods on Feras," Quayam said, "We need Thristen along as our doctor."

"To be fair," I said, "his doctoring is not the first reason I would give for wanting him to come."

Quayam shrugged his shoulders.

"Why don't Dad and Thristen go, and leave you behind, Mom?"

"If we go, then all three of us go. I'm not staying behind. Three people make a better group than two. That's how we like to work. And your father and I are not going to be apart for a year, and Thristen is not going to stay behind just because his god-daughter wants him to."

"Then you should take me too, because I don't want to be away from you for a year."

I smiled. "Last month you told me to go away and never come back."

"I was joking."

"You're not coming," Quayam said, "It's too dangerous. I'm sorry."

"I bet you are."

"I am."

"This time," I said, "you won't have to go to Careem's office to talk to us. You can keep a bridge to us here yourself. We'll talk every day, not just for a few minutes, but for an hour at a time."

"Big deal."

Quayam said, "I was thinking of buying you a camera that can take pictures through a space bridge, so you can photograph the places we go."

"Great."

"The pictures can go in my write-up," I said.

"If they're up to standard, that is," Quayam said.

"I know how to take photographs."

Quayam poured himself another glass of water.

"So are you going or aren't you?"

Quayam said, "We have to be certain that the facts presented by Nicholas are correct."

"What facts?"

"The times and locations of the conjunctions. We have to consult a router."

"When will that be?"

"Tomorrow," I said, "Careem recommended one to us, and I'm going to visit her tomorrow morning. Would you like to come?"

"No thank you. I'm going riding with Thristen."

"Very well."

Romayne got up from the table. "I have to go now, I'm late. I'm supposed to meet my friends in the Triangle."

"Enjoy."

"Will you be back for supper?" Quayam said.

"I don't know."

"We're going over to Thristen's for supper, so join us there if you want to."

"Okay."

She left. Quayam and I looked at one another.

"She'll be fine," he said.

It was the end of December 2475. I was forty-two years old. I had been taking longevity drugs for six years. Despite their name, longevity drugs do not make you live longer, they merely make it possible for you to keep your body resilient and strong. Unfortunately, the drugs are expensive, and have a number of unpleasant side effects. They turned my hair white, for example. Now I dye it red, which is my natural color. In a few more years, my skin, which is already fair, will become pale and acutely sensitive to the sun. Eventually, my green eyes will turn gray. The whites will have a hint of pink in them.

Quayam does not take longevity drugs because he has no need of them. In 2475, he was one-hundred-and-seventy-nine years old. He is a homo hortulanus, or elf, in the same sense that Thristen and I are homo sapiens, or sapiens. Quayam's natural life span may be long, but in practice he is unlikely to live any longer than Thristen and me.

Few people die of old age in our line of work. In Pakesh, when we fill out a form giving our occupation, we write 'adventurer', which is to say that we rescue people, capture criminals, guard archaeologists, and fetch things from far-away places. If Quayam wants to live out his natural life span, he will have to retire, stop riding horses, refuse to climb trees, and never swim in rivers. Most elves are happy living like that. In fact, they insist upon it.

That evening, we stood in Thristen's kitchen, watching him cook. He had his back to us, stirring a stew.

"She's entering adolescence," he said, "It's a difficult period. I'm sure you will all work together to understand how you feel about all the different events taking place in your lives, because you're caring people, so each situation will be different, but it will all work out."

"I keep thinking that she's only eleven," I said, "and it's not right to leave her."

"She's eleven, but she acts like a thirteen-year-old, and looks like one too."

"She's half-elf," Quayam said, "elves grow up quickly."

"How do you know what a thirteen-year-old acts like?" I said to Thristen.

"I teach them stick-fighting at the gym," Thristen said. "And eleven-year-olds too." He took the lid off the rice pot and a lazy cloud of rice-flavored steam emerged. "So don't worry about it. You left her for months at a time when she was younger, so this is just longer. It always worked out."

"Celia will look after her," Quayam said.

Celia is the older of my two younger sisters. She is unmarried.

"I'm not certain she's coming," I said.

"She always comes," Thristen said.

There was a knock on the door.

"Maybe that's Romayne," I said.

I was right. Thristen answered the door and led her into the kitchen.

"Hello, sweetheart," I said.

"Don't call me sweetheart."

I met Quayam in 2462. Thristen, he, and I worked together for a year or two. It was lots of fun. I was more experienced than they were, but it was clear to me that they were going to do well in the business. By the end of the year, I was thinking about how many children Quayam and I should have.

"As many as we are fortunate enough to have," he said.

"Four?"

He laughed.

"What are you laughing at?"

"I'm thinking how funny it would be to have four children."

"Would you like it?"

"I guess so, but it isn't going to happen."

"Why not?"

"I don't know. I wish it would, but it won't."

We sat in silence for a moment.

"I'm missing something here," I said.

"Oh?"

"How did your parents plan their family? Why did they choose to have you and your sister one hundred years apart instead of close together?"

"What makes you think they chose to have us at those particular times?"

"Well, your mother had her sterilization reversed, had your sister—"

"Elf women never get sterilized," he said.

"What controls your population?"

"We have as many children as we can."

"Your parents had as many children as they could, and they had only two children in the five hundred years they lived together?"

"And their friends congratulated them on their good fortune. I come from a particularly fertile family."

I had my sterilization reversed soon after. If Quayam and I never had any children, I did not want it to be because I was hesitant. When I explained my decision to Quayam, he said, "You want it to be my fault exclusively."

"Not at all. If we don't have any children, so be it. We can always adopt them."

Three months later I was pregnant. Quayam thought the child was not his.

"It is yours," I said.

"Great."

"If you think it's someone else's, we should talk about it. I don't want that hanging over my head for nine months."

"Why?"

"I don't want you to be suspicious of me."

"Suspicious of what?"

"You know what I'm talking about."

"No I don't."

"Suspicious that I have a lover."

"Well, what if you do?"

"You'll be jealous."

"Not really."

"Are you insulting me?"

"No, I'm being respectful."

I was shouting. "How is that respectful?"

Quayam frowned. "Being with me for the next fifty years, you give up other men for the rest of your life. That doesn't seem fair."

"How noble of you. But don't try to tell me that you can be jealous or not jealous depending upon whether you think it's appropriate or not. If you love someone, you're jealous."

He shrugged.

"So why aren't you jealous?" I said.

"What's the point? It's pure selfishness. Aren't people ashamed to be jealous?"

"It's generally the case, at least among sapiens, that people who love one another are jealous. It's nothing to be ashamed of."

"Well, I'm sorry to disappoint you."

"I'm not disappointed. I'm uncomfortable."

"How about this, then, if you touch any other man," Quayam said, "I'll kill him."

I smiled. "That's better."

When Romayne was borne, it was obvious that Quayam was her father. She has his high cheekbones and his blue eyes. Quayam was astonished, and very glad. But he was not relieved. I believe he was absolutely candid when he said that he would not be jealous.

The first few years I spent looking after her were happy ones. Quayam was with us in Pakesh most of the time. We went on a seven-month vacation with Thristen and a nanny, and I bought an apartment and two small businesses.

Eventually, however, Quayam started going away for months at a time. In the evening I would find myself sitting at home, wondering if he was alive, and if he was, whether he was being faithful to me. When he returned, I would chastise him for being away longer than he had led me to expect, and I would demand that he not leave again for another six months. He listened, but he never said much.

When Romayne was six, Celia told me I could not continue as I was. I was making everyone miserable. When Quayam came back a week later, I told him I was ready to leave him. I wanted to sell the apartment and my businesses, and go home to Varay. He nodded, and walked out. Two days later he came back.

"Okay. But before you go, come on one last job, a short one: two weeks. We rescue a young woman and come home. It's great money: half a million split between us. Just leave Romayne with Celia and come."

"Half a million between two of us?" I said.

"Four of us. Thristen and Bolus are coming too."

Bolus is another partner of ours, a wizard.

"I'll make more in two weeks than I made in the last two years."

"I know."

"I'm going to need the money after I've left you."

"Exactly."

So I went with them. When we returned, Romayne was angry with me for a few days, but she got over it. In the evenings, when she was asleep, Quayam and I talked and laughed. You may think that I am a bad mother. I will not argue with you. But I would have been worse if I had stayed at home. As it is, Quayam and I are still together, and I have no regrets about our trips. I have enjoyed them all. And despite our being away half the time, Romayne has grown up to be a healthy, smart, and capable young woman.

When I woke up the next morning, Quayam was already out of bed. I heard him talking to Mary, our housekeeper.

"It's fine."

"Sir, the egg is over-done. I thought you said hard-boiled."

"It's fine."

"I'm going to make you another one."

"Will you stop that? I'm eating the egg, see? It's delicious."

There was a short silence.

"Please sit down."

Mary pulled a chair up to the table.

"I'm going to say this once and once only."

"What, sir?"

"You have to relax. I don't want to wake up in the morning and see somebody who's not relaxed. I don't want Romayne to wake up in the morning and see somebody who's not relaxed. Part of your job is to be relaxed. If you're not relaxed, I'm going to fire you. Do you understand?"

"Yes sir."

I coughed.

"I don't know what you're problems are, but whatever they are, Gristel and I will help. We're nice people. But don't talk to Romayne about your problems. Do you understand? Never talk to Romayne about your problems."

"Yes sir."

"Good."

Quayam put his cup down on the table.

"Make some coffee for Gristel, she's awake."

He ate his breakfast, and I lay in bed waiting for my coffee. The sun shone through our bedroom windows, and landed on the tapestry opposite our bed. It depicts the adventures of a gallant knight who resists temptation, kills an ogre, and survives hunger and thirst. In the end he earns the favor of his king and his god.

The tapestry is old; something Quayam picked up on one of his earliest adventures. At first its pictures seem childlike, but after Quayam and I had looked at it for long enough, we agreed that the over-sized faces showed the knight's states of torment so distinctly that the style must have been deliberate, and that the artist was a great master in her time.

Mary came out of the kitchen with my coffee.

"I'll give it to her," Quayam said.

He brought me my coffee and sat down on the bed. I held the cup in both hands.

"The trials of the knight are enviable in a way," I said, "because they are so straightforward, and end with his apparently permanent contentment."

He turned and looked at the tapestry.

"I agree," he said.

I blew on my coffee. "I'm going to see the router this morning."

"Good. I'd like to come but I think I will go ride with Romayne and Thristen."

"That will be nice."

"I think we'll go to the orchards."

"Lovely. Perhaps you could make arrangements for the horses while we are away."

"I will."

"Assuming we go, of course."

"Of course."

"Good."

He nodded.

"Those were some stern words you had for Mary," I said.

"I had to make sure she understood. We'll be away for a year."

"We'll be in touch."

He frowned. "Let's not debate my style, okay?"

"I'm sorry. You're quite right."

He got up to leave.

"Where are you going?"

"I don't know."

"Well, stay here."

He sat down again. "Okay."

The router's office was above a fishmonger, in a yellow-plastered building on Kurdestan Boulevard. Pakesh is a thousand kilometers from the sea, and it is not easy to find fresh seafood. At that time, there were only two fishmongers in the city, and they sold mostly fresh-water fish caught in the Fen River a few hundred kilometers to the northwest. I like fish, so I knew both fishmongers well. When I arrived, this one was standing in the shade beneath his awning with his fish arrayed before him covered in crushed ice.

"Mrs. Virage! I have something here just for you, how fortunate that you came by." He pointed to the contents of an open crate. "Here, look, shrimps, giant shrimps, flown this morning from the ocean, just for your table."

"Flown this morning?" I said.

"This morning, great lady, to give you a taste of the sea."

"Flown how?"

"By hippogriff, great lady, from Karadan." He picked up a shrimp and held it in front of my face. "The giant shrimp, available only at this time of year. So sweet it must be tasted to be believed."

We admired the shrimp. "It does look lovely," I said.

"But alas, Mrs. Virage, there is one thing I must tell you, and it pains me to do so."

"And what is that?"

"They are most dreadfully expensive."

"How much?"

"I am almost ashamed to tell you."

"But please do anyway."

"Two hundred dollars a kilogram."

"That much?"

"Yes."

"What a pity, what with us fallen on hard times, and my daughter being so hungry."

"Alas, I knew it would break your heart." He put his hand on his chest. "That is why I didn't have them delivered to you as soon as they came in."

"Oh well, when I'm done upstairs, I'll come down and buy something more within my means. A small carp, perhaps. It'll be better than nothing."

"Far better than nothing, Mrs. Virage, far better."

I went upstairs and knocked on a peeling green door. A woman of about sixty opened it. She wore a rumpled white smock and held some coins in her hand.

"Oh, I thought you were the soup boy."

"You did?"

"Well, never mind."

"Ladan Shirazi?"

"Yes."

"Your cousin Careem recommended you to me."

"How gracious of him."

"Should I come back after lunch?"

"Not at all."

She stood back to let me in.

"Thank you," I said.

I stepped inside, and she closed the door behind me. Her office was ten meters square and full of maps. They were hanging on the walls, piled on the table in the center of the room, and stacked on the bookshelves. Scattered across every surface was a profusion of notebooks, rulers, compasses, candles, and pencils. In the shadows under the table was a stack of unwashed plates, and in the corner by the door was a pile of dirty laundry.

I walked to the table and looked at the maps lying there. They were of worlds that I had never heard of, with names like Overlook, Terminus, and Draconia.

"Won't you sit down, my dear?"

She pointed to a leather armchair next to the table.

"Thank you." I sat down.

Ladan sat on a stool and tucked her hair behind her ears. "What can I do for you?"

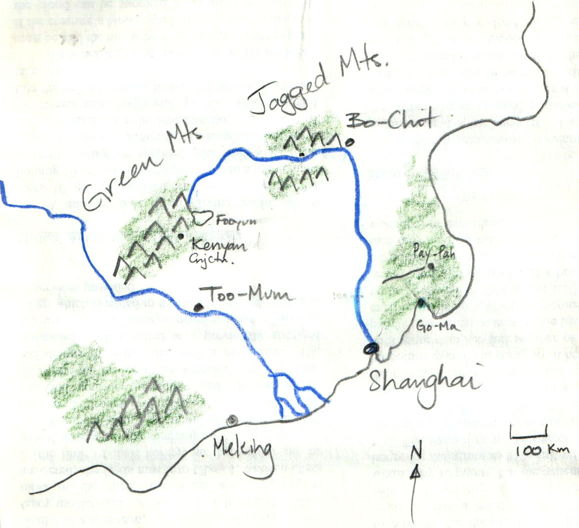

"I want to go to a town called Foo-Yun in the north of a country called Lomein on the planet Feras."

"And back again?"

"Yes."

She stood up and walked around the table to a large, colorful map on the wall. "Feras. In the Northern Hemisphere or the southern?"

"Northern."

She examined the map. "Here's Lomein, but I see no Foo-Yun."

I stood up and joined her. "How about some Green Mountains?"

"Green Mountains." She examined the map. "Here they are."

She pointed to a range of mountains marked on the map with shades of brown and purple. "Let me see what we have for that part of the planet."

She returned to the table, dragged a large book towards her, and opened it. She leafed through pages that were filled with tables and maps. "What an exciting book," I said.

"It is Kambiz's Almanac of Conjunctions, my dear." She found the page she wanted. "Haven't you seen one before?"

"I can't say I have."

I looked over her shoulder. "What do the numbers mean?"

"I'd love to explain them to you, dear, but I'm rather busy right now, so forgive me if I don't."

I went back to the armchair and sat down.

"There are a lot of routes here. It will take a couple of days to go through them."

We had promised Nicholas we would decide the next day.

"I need an answer tomorrow."

Ladan closed the almanac. "Sorry, my dear."

"How much do I have to pay you to do it by tomorrow lunch time?"

"I would have to stay up half the night, dear girl, for the second night running."

There was a knock on the door, and Ladan rose to answer. It was the soup boy. She paid him and took her soup. He turned away immediately, and she closed the door.

"Where were we?" she said, and put her soup down on the corner of the table. "That's right, you were asking me to stay up half the night."

"So it would seem."

"I'm tired, my dear. I won't do it for less than five hundred dollars."

"Fine." I handed her my card. "Come to lunch tomorrow. I'll send our carriage to pick you up at eleven-thirty."

She looked at the card. "Gristel Virage, what a nice name, and a nice part of town." She looked up at me. "Very well, I will see you tomorrow."

I stood up. "I look forward to it."

"How long do you want to spend in Foo-Yun?" she said.

I stopped to think. "Give us a month."

Ladan arrived shortly after midday, having kept our cab waiting for twenty minutes. I showed her out to the veranda and introduced her to Nicholas, Quayam, Romayne, and Thristen. Our agent, Careem, was there too.

"My dear cousin," she said.

They embraced.

"Won't you sit down?" I said.

She did.

"Did you get any sleep?" Romayne said.

Ladan laughed. "Enough, my dear, we old ladies don't need much sleep, you know."

Thristen poured her a cup of tea. "Did you find any good routes?"

"Straight onto business, then." She took some notes from her bag.

"If you'd rather wait, that's fine."

"Not at all, dear. Let me see. The Jamsheed Conjunction starts on the fifteenth of January. It occurs in the desert two hundred kilometers south of here, and will take you to Solomon, an island on Feras. From there you can sail, about a week, to Shanghai, a port on the coast of Lomein. From Shanghai it's five hundred kilometers overland to Foo-Yun."

"I told you," Nicholas said.

"Thank you, Nicholas," I said.

"The way back is through the Kenyan Conjunction, which opens on the twenty-fourth of June." She looked up at me. "A stroke of luck, really."

"Yes."

"You have six months to get from the Jamsheed to the Kenyan."

"How long does the Kenyan open for?" Quayam said.

"Five days. Your wife told me you needed a month in Foo-Yun, so I dismissed the Kenyan as a means for your arrival."

"How far is it from the Kenyan to Foo-Yun?"

"I don't know, I can't find Foo-Yun on the map."

"What's the farthest it could be?" I said.

"I have no idea."

"Richard seemed to think it was a few days ride," Nicholas said.

"How long did you say we have to get from the Jamsheed to the Kenyan?" I said.

"Six months."

"And it's five hundred kilometers overland?"

"That's right, and a little farther across the ocean."

She took a roll of paper out of her bag and spread it on the table. It was a black-and-white, printed map. "Here's a map of Feras. It is small-scale, unfortunately, but it shows the Jamsheed here on Solomon Island, Shanghai and Lomein on the mainland to the north, and the Kenyan in the north of Lomein as well."

"Can you sail right across the ocean from Solomon?" Quayam said.

"Do you mean, are there any kraken in the waters? No there are not, my dear, so you can sail to your heart's content. But there may be pirates."

She took out another map and spread it over the first. It was of our planet, Clarus. "The Kenyan takes you to this point on Leaena." She pointed to a spot marked on the continent south of our own. "You can sail from the north-eastern shore of the continent all the way back to Karadan without entering kraken-patrolled waters."

Karadan is the nearest seaport to Pakesh.

"The journey north from the conjunction to the coast of Leaena is across grassy plains. It will be cool and occasionally rainy at that time of year."

"What time of year?" Romayne said.

"Mid-June."

"This year or next year?"

"This year, dear, if you add up the months, you will see that it all works out."

Ladan turned back to the map. "According to reports from previous travelers, the locals on Leaena are primitive, but will give you food and water for gold. By foot it will take you two to three weeks. The journey back to Karadan by sea is four to six months, depending upon the boat you take."

"I'm not so worried about the locals on Leaena," Quayam said, "It's the locals in Lomein that concern me."

"I am afraid I cannot tell you much about them, my dear, other than that the country is heavily populated, as are many countries on Feras, and that their culture will consequently be skewed to allow them to live comfortably in the company of so many others like themselves."

"Do we have any alternative routes?" I said.

"I looked for double and triple links, but there were no good ones."

"What's a triple-link?" Romayne said.

"A triple-link," Ladan said, "might be Clarus to Comitor, Comitor to Vagor, Vagor to Feras."

"Why do that?"

"Sometimes it's quicker."

"How can it be quicker?"

"If the conjunctions are close, and occur soon after one another, even a five-link can be quicker than a one-link."

"Oh," Romayne said.

"Can we keep these maps?" Thristen said.

"Of course, dear, they are part of the service. And these notes are for you, too. They give all the dates and distances, as well as the comments and annotations from the Almanac."

She collected the notes and maps into a neat pile and stood up.

"I am most dreadfully busy, my dears, so I hope you won't mind if I go back to my office. If you have any more questions do come and see me, and I will be glad to answer them. I think, however, that you will find my notes quite comprehensive."

"I'm sure we will," Thristen said.

"Won't you stay for lunch, at least?" I said.

"No thank you."

"But we're having giant shrimp, so delicious it must be tasted to be believed."

"I'm afraid I'm allergic to shellfish."

"How unfortunate."

Ladan smiled. "Not when you live in the middle of a desert, my dear."

The Kenyan Conjunction was why Richard was in Foo-Yun in the first place. He intended to buy jade in the Green Mountains and bring it back through the Kenyan to Clarus. The price of Jade had tripled on Clarus in the previous two years because supply from the Green Mountains via the Jamsheed Conjunction was slowing down. This was the sort of business venture by which Richard had made his fortune.

After lunch, I took Careem aside. "I think we'll do it, but let's leave the paper-work until tomorrow morning at your place. I don't want to talk about money in front of Romayne."

He stopped smiling and nodded.

"I know we promised him an answer today," I said, "but we need to talk about it some more. Is that a problem? You said that he had been talking to some of our competitors."

He frowned. "He will not be happy. He is anxious. But he will wait, what is the hurry? So don't worry about it."

He looked up at me. For a moment I saw in his eyes the young man we had met in a tiny office years before, when we, too, were young and eager for success. Now his face was rounder, and marked with the lines of his smile. "I will take Nicholas away and let my children play with him."

"Your children like him?"

"They like every client. It is their obligation to their father."

I smiled. "Is he good with the children?"

Careem frowned. "You ask the strangest questions, Gristel."

"But does he like playing with children?"

"Of course. Everybody likes playing with children."

We stood in silence for a moment.

"Gristel, Nicholas is a good man."

"You think so?"

"I am certain of it."

"Then he will wait another day."

"Of course."

"Thank you."

Careem bowed. "I am at your service."

Later that afternoon, Quayam, Thristen, Romayne, and I sat around the patio table. Spread out on the table were Ladan's maps, and several others Thristen and Quayam had obtained.

"Richard is going to be delighted," Quayam said, "We rescue him and take him back through the same conjunction he was going to take anyway."

"Minus his jade," I said.

"Don't underestimate Richard Crockford," Thristen said.

Mary came out with tea, strong and black in small glasses, with sugar cubes in a bowl. Quayam dropped three cubes into his glass and watched them dissolve.

I said, "I want to talk about going out through the Kenyan, grabbing Richard, and coming back before it closes. If we can do that, we save a lot of time and effort."

"We wouldn't get back any sooner," Thristen said.

"But we will spend less time away from home."

"It will take four months to sail to Leaena," Thristen said, "and another month to trek to the Kenyan. If we go through the Jamsheed we have two weeks ride across the desert, then six months overland to the Kenyan. Five months or six and a half months, not much difference."

"It's one and a half months different," I said.

Romayne watched me.

"And we have to come back the same way," Quayam sais. "if we sail to the Kenyan. That's no fun, coming back the same way as we went out."

Thristen reached for the sugar. "I see what you're saying, Gristel." He put two cubes in his glass. "But the most important thing is the mission. We do not want to be away from home longer than we need to be, but I don't think it will be easy to get Richard out in the five days the Kenyan is open."

"You could balloon in," Romayne said, "grab him, and balloon back again."

Quayam can make balloons out of conjured matter. Whenever we can, we travel that way. It is fast and comfortable.

"We need the right wind to get there," Thristen said, "and if we have the right wind to get there, we may not have the right wind to get back, and we will be stuck."

"What if you take horses?"

"We don't know how far it is. You heard Ladan; it could be two day's ride each way, with only a day to get him out. We don't have enough information to do it that way."

"We will be seen and expected," I said.

"Yes," Quayam said.

"So take hippogriffs," Romayne said.

We did not own hippogriffs at that time, but they are freely available in Pakesh. They fly overhead at all hours a day.

"I'm not sure you can take griffs through to Feras," I said.

"That won't work either," Quayam said, "Ladan said the country is heavily populated. Lots of towns. Lots of cities. We'll be flying around looking down at them. Which one is Foo-Yun? Is it this one, with the golden palace, or this one, with the silver palace? I don't know, let's go and ask them. Excuse me, is this Foo-Yun? Can we land in the palace with our swords please? Do you have any foreign prisoners? We would like to shake their hands, no of course we aren't going to try any funny business, what do you mean you haven't seen griffs before?"

Thristen smiled. He picked up Ladan's notes and looked through them. "No griffs allowed through the conjunction. It says right here, 'no alterations'."

"A griff is an alteration?" Romayne said.

"They're certainly not natural."

"I thought they were native of the mountains."

"That's where we breed them, but they have never survived there without the help of mankind."

"So," Quayam said, "There you go. No griffs."

We sipped our tea and looked at the maps. Mary brought out a plate of sweets and we moved it around on the maps until Thristen put it on the ground.

"It does not seem to me any easier," I said, "for us to go overland across a densely populated country and arrive without suspicion at the palace of a barbaric warlord."

"Where did you get the information about him being barbaric?" Thristen said.

"I don't know. That's my impression, what with the beheadings and all."

"We could travel in disguise," Quayam said.

"I don't think so," Thristen said, "Ladan's notes say the Lomese are small and slender, with jet-black hair, tiny noses, fair skin, and brown, sharp-edged eyes like those of the Chiin here on Clarus."

"They are probably from the same Terran stock," Quayam said.

"And here we have Gristel, a red-haired, broad-shouldered woman, and Quayam an elf with brown hair, blue eyes, and pointy ears."

"And then there's you," I said. Thristen is one hundred and eighty centimeters tall and weighs around a hundred kilograms and can bench-press over one hundred and fifty kilograms one time.

"At least I have straight, dark hair," Thristen said.

"And blue eyes," Romayne said, "and a not-small nose."

"We all have not-small noses," I said.

I unrolled a map of Feras that Thristen had purchased the day before, and tried to find the Green Mountains.

"You could dress up as pilgrims," Romayne said.

"I could wear a hat to hide my ears," Quayam said, "Maybe nobody will know I am an elf. But they will know we are foreigners no matter what we wear."

"They will know you are an elf from your eyes," I said.

Quayam raised his eyebrows.

"They slant downwards, Dad."

"So do yours," he said.

"Of course they do, Dad, I look like you."

I once tried to measure how much lower the inner sides of Quayam's eyes are compared to the outer sides, but I could not find a good place from which to measure. I should try it again with a spirit level. The difference cannot be more than a couple of millimeters, but it is still noticeable. If you did not know he was an elf, you would look at him twice and think there was something odd about him. Not something unattractive, but something odd.

I said, "Richard Crockford and his two Endan companions made it all the way to Foo-Yun. So we know it can be done."

"We know it can be done by Richard Crockford," Quayam said, "But Richard Crockford is a master-traveler."

"We can do it too," Thristen said, "We've done a fair bit of traveling on our various missions, trading and talking to people to find out the information we need."

"Richard speaks a dozen languages," Quayam said, "He studies the countries he is going to for months, or even years, before he goes. He knows exactly how to deal with the people, and always has connections to take advantage of."

"We can do the same," Thristen said, "We have two weeks here to study. We can start learning the language. We can get more maps, and find out if anyone trades with Lomein. We can ask Careem, we can—"

"Get letters of introduction," I said.

"Letters of introduction, and information from traders. There's a lot we can do before we leave to make it easier when we get there."

"If you dress up as pilgrims," Romayne said, "It won't matter what you look like because everyone will know that you are going somewhere holy, and you can hide your swords under your robes."

"That's a good idea," I said.

"When we get there," Thristen said, "We can examine the particulars of the situation and decide what to do."

"I agree," Quayam said, "But it isn't going to be easy."

"If it was going to be easy, Richard would not be paying us two—"

"That's right," I said.

"He's paying you?" Romayne said, "I thought he was a friend and you had to do it."

"Business is business, darling," Quayam said, "And Daddy has to have money to buy you expensive presents."

The next morning we signed a contract committing us to an attempt to rescue Richard Crockford from Feras. Payment was contingent in upon our success. We were to leave in two weeks. We assigned Quayam the duty of learning Lomese. He found some books in the library and declared the language to be tonal.

"What does that mean?" Romayne said.

"The pitch is part of the meaning," Quayam said, "Unlike Ursian, in which the pitch is part of the emphasis."

Romayne nodded her head, "Oh."

"Like this," I said. "If you say 'uh-huh' like that, a low note and then a high note, it means 'yes' to us. But if you say 'uh-huh' the other way around, with the low note second, it means 'no'."

"It's 'uh-huh' and 'huh-uh'," Romayne said, "Not 'uh-huh' and 'uh-huh'."

"I guess you're right," I said, "Oh well, but you get my point."

"Sort of."

"That makes it tough to learn," Quayam said, "For me."

"You must be excited," I said.

"I'm not sure I can do it."

"I have faith."

Shortly before we left, Quayam and I gave one half of a space bridge to Romayne. The bridge itself was a circular surface, about one centimeter in diameter, held in a metal ring. I kept the other half for myself. Romayne, on the other side of the patio table, looked through her half and saw me looking back at her through mine.

"Cool. Can I take it to school?"

"Take it everywhere with you. Here is a case for it." I slid a small leather pouch across the table. "Your half is covered on both sides by a sibilant membrane. It transmits sound, although with some loss of volume, and you can see through it perfectly, but it won't allow anything solid to enter the bridge."

She touched the membrane hesitantly.

"Be careful with it," I said, "Don't puncture the membrane or air will rush through."

"Why?"

"Because we will be on another planet with a different atmospheric pressure, or at a different altitude."

"Will it blow up the house?"

"No, it will make a noise like a trumpet. It's worse if the air rushes into the bridge, because then your sleeve might be pulled in, or anything else that's light-weight, and any matter passing through will be atomized."

"Does it make a poison gas?"

"I don't think so, but it can be smelly."

"I'll be careful."

"If you do puncture it, take it to Careem and he will get a wizard to put another membrane on it. You must take it to him once a month for tuning anyway. It needs to be tuned so it keeps going."

"Okay."

"We'll talk every day," I said.

"Okay."

The space bridges we carry around with us are not as large or as accommodating as conjunctions. Conjunctions, quite apart from being several meters in diameter, will allow any type of matter to pass through them, be it chemical, spirit, or conjured. You can take a space bridge through a conjunction, and have it working on the other side. No other type of bridge will do that for you.

The bridges we carry around are 'atomic bridges'. Wizards make them for us, or sometimes Quayam makes them, but his last for only a few hours. The ones we get from wizards can last forever if wizards tune them regularly.

Anything you put through an atomic bridge gets broken down into its constituent atoms, or so I am told. Nevertheless, our atomic bridges are great for talking, and you can see through them. It is like looking through a hole in the universe to another place.

"If your bridge collapses," Quayam said, "Careem will have another one for you. We are leaving three with him, and one with you. We also have bridges to summoning agencies on Olympia."

"Okay."

"And I have a present for you."

He went inside and came out soon after with a large metal contraption, a wooden box, and a leather-bound book. He put them all on the table and pushed the contraption towards Romayne.

"Camera with space bridge adapter, viewing window, and speaking tube."

He pointed to the box. "There are a hundred films in there. You can buy more if you need them."

"Wow," she said.

"May I have your bridge?" Quayam said.

Romayne passed him the metal ring with the bridge inside it. Quayam uncovered a slot in the side of the camera. "Slide it in here like this."

He pushed the bridge ring into the slot and closed the cover. "Look through here."

He looked through the window on top. After a moment he reached into an opening at the back of the camera and pulled out a black silk sheet. "You need this to see properly."

He put the sheet over his head and the camera. "Ah. It's working."

Romayne looked under the sheet. I held up my half of the space bridge and made a face at it.

"I can see the garden," she said.

I turned the bridge around.

"Woah!" Romayne said from under the sheet, "That made me dizzy."

I made my face again.

"Hello Mom."

Romayne took the sheet off and looked at Quayam.

"It really takes pictures?"

"I hope so."

"How do you put the film in?"

Quayam picked up the book and gave it to her.

"The manual."

Brought to you by Ahmed and Ahmed Photography, Pakesh's largest supplier of cameras and photographic film. In our display room at 178 Mohandess Boulevard, you'll find the finest photographic equipment in the world. If you want to buy a camera, come and talk to us. We'll be glad to help.

On January 8, 2476, we left Romayne with my sister, Celia. I will not tire you with a description of our goodbye, suffice to say that it was a tearful one. We joined a caravan of horse-drawn wagons bound for the Jamsheed Conjunction. The leader of the caravan, a man named Maimonidese, hired us as extra guards, in addition to the ten camel-riding men-at-arms he had already contracted before we approached him.

Maimonidese was concerned for the security of his caravan because, three years earlier, a caravan returning from the conjunction had disappeared. Maimonidese believed the caravan had been attacked by bandits, leaving no survivors. I did not try to persuade him that the more likely explanation for the disappearance was a sand storm. In exchange for our protection, the caravan would feed us and provide us with tents to sleep in at night. With Quayam, Thristen and I in their company, they felt safe enough to embark without waiting to unite with other caravans. Large caravans are safer, but they are also more difficult to supply.

Despite living in Pakesh for nearly ten years, I had never been far into the desert south of the city. When I had traveled south from Pakesh, it was always on the highway on the western edge the desert, running along the foothills of the mountains that separate the desert from the sea. But now we were going south-east from the city, straight into the heart of the desert. There would be no caravansaries, nor even a road.

Our companions had come all the way from Equina, a country known for its horses. The slow, steady, beasts that drew the wagons were large, strong, and shiny. There were eleven wagons in all, and twenty-eight people counting us and the ten guards. All the wagons were covered, and each had a bench behind the horses that would sit two people comfortably. It was on these benches that we were to spend much of our time for the next six days.

Our final days in Pakesh had been tiring, rushing about making sure we had what we thought we needed for our journey, trying to find and befriend someone with allies in Shanghai, and worrying about leaving Romayne. But once we left the city, there was suddenly nothing to do.

I sat next to Maimonides.

"Why didn't you exchange your horses for camels," I said, "They would drink less water."

"There is no need. There is always water along the way for us. The desert people are bringing it. I don't know where they are bringing it from, but they are bringing it. When you will be arriving to the conjunction there is much of water, and even the camels must drink. They are enough bringing water for you to have a bath if you want to. And when the conjunction is open, the water is coming from Solomon. All that the horses can drink, they bring."

Maimonides held the reins of the two horses that pulled the wagon in one hand. I was sitting at the edge of the seat because the rest of it was taken up by his ample backside.

"But you know, Gristel, you are right, it is bad with the horses in the summer. It is better now, in winter. In summer it is too hot. Last time the heat was terrible. We must travel at night so we do not get burned by the sun. Then there is a sand storm. A big sand storm that is going from one sky to the other."

He took out a big red handkerchief and wiped his brow. "What a terrible time it is then!"

He tried to get the handkerchief back into his trouser pocket, but the fabric was stretched too tight, so he tucked it into his shirtsleeve.

It was late morning. We had left the last habitations around Pakesh behind. The desert stretched before us, a shimmering expanse of packed, brown, dirt. We followed a trail newly worn by the passage of camels, wagons, and men.

"We do good business there. Many of us come every fifteen months. It is one month each way, and one week for trading. But I think I am coming only in winter in the next years."

Maimonidese owned five of the caravan's wagons

"What are you carrying?"

"I have mink, linen, and one hundred kilos of aluminum."

"A hundred kilos! You're a rich man, Maimonidese."

"I will be, but now I am in big debt."

"What will you buy?"

"I try to get silk and jade."

"Does the jade come from the Green Mountains of Lomein?"

"I don't know where it is coming from, but it is more expensive every time. Ten years ago we are buying it for twenty gold pieces one kilo, now we are paying forty."

"And how much do you sell it for?"

"Oh, my dear, you ask questions!" He pinched my cheek. "And what do you have with you?"

"All that we think we will need for a long journey across Feras."

"And what is that?"

"Cash, medicine, bandages, journals, wire and tools for our armor, lots of matches, a change of clothes, our oilskins, insect repellant, maps, tobacco, rolling papers, blankets, salt, cooking pots, utensils, canteens, a lantern, towels," I paused, "more medicine, and more cash."

"No perfume, no soap?"

"None."

"I will give you some, to remember me with. I have some of the finest of the soaps in my wagons, and the best of perfumes."

"Thank you, Maimonidese, I will be glad of them."

It was hot during the day, but not too hot. I made a space for myself in one of Maimonidese's wagons where I could sleep in the shade. But most of the time I sat out in the sun, with a broad-rimmed hat on and a long-sleeved shirt and baggy trousers. When we left Pakesh, Maimonidese had suggested we wear our armor while guarding the caravan, but we refused, and packed it in one of his wagons instead. On my feet I wore boots. I would have been more comfortable in sandals, but I prefer to wear boots.

I had to tie my hat to my head with a ribbon because the wind blew steadily all day out of the west. The wind kept us comfortable, but it dried us out too. On the second day, I forgot to drink water in the morning, and at noon I felt dizzy. Quayam had to help me into my wagon and cool me off with a wet sponge.

After three days, I was sitting and looking out at the desert in silence for hours at a time. Once, when a low hill appeared on the horizon to the east, I caught up with the wagon Quayam was sitting on to point it out to him. Eventually, the emptiness and desolation became familiar, and I found myself looked forward to our next encounter with the desert people.

Staring at the desert, it was hard to imagine anyone living there. But every couple of days we would see half a dozen large tents by the side of the path ahead of us. There was never anything to distinguish the places they picked to meet us, other than their presence. Where did they come from? They had water, goats, chickens, and dates to sell, but what did the goats eat? There were no plants, and no date trees either. But we came out of the desert from the north and they would be there, standing outside their tents, and the place we met would be a special place, a place where two groups of people came together, with nothing else in the desert around them as far as you could see, and certainly nothing to compare with the bright clothes and smiling faces of the desert women, and the handsome, weathered features of their men, who stood back near their camels, their swords hanging by their sides.

At a command from Maimonides, our caravan would stop fifty meters short of the camp. He and the cook would get a dozen empty water skins from the back of a wagon, walk to the tents, and spend half an hour deciding what to buy and how much to pay for it. I would watch the desert people from my bench, and try to hear what they said. When they were finished, Maimonides and the cook would carry their purchases back to the caravan themselves. It would take several trips, one trip with a goat and a chicken, and one with a sack of flower between them, and several trips with skins of water. Then we would be on our way again.

After one such encounter, I said to Maimonidese, "I would like to meet them."

"They do not like it that you meet them. They are here to sell, not to talk. They look down on us. We have fat faces and drink too much water. They like to fight. I do not. You should not talk to them. It is my command."

As we moved past their camp, however, I waved to the women and children, and they waved back and smiled.

Our main meal was at night. As soon as the sun went down, we pitched tents and waited while the cook prepared dinner. We ate all together; thirty of us sitting on an enormous cotton sheet, facing the food laid out on the inside. It was an Ursian arrangement, well-suited to the desert, but the cook was Equinan. We ate stew, roast meat, unleavened bread, and boiled potatoes, and we drank dark red wine from small glasses. We did not talk much because we were always hungry after a day with nothing to eat since breakfast.

But after supper, the air cooled, and we sat around and relaxed. The stars were clear and bright, with the galaxy a wispy band of green and pink across the sky. Maria, one of the merchants, had some telescopes, and one night she set one up for us at Thristen's request. While she was adjusting its tripod, Thristen examined the instrument's brass housing.

"I like the engravings."

"I have several of them for sale. Three-inch achromatic refractors."

"Sounds impressive."

"Would you like to buy one?"

"I'd like to, but I won't be able to carry it."

Maria squinted through the eyepiece. "I could leave one for you in Pakesh on my way home."

"Well…"

"Ah!" she said, "This is Feras's sun, if I'm not mistaken. Take a look."

We all looked. A small white dot moved slowly across the field of view. Maria claimed that this motion was a feature of Clarus's rotation, and not the mounting tripod sinking into the sand.

Thristen said, "Maybe people going to the conjunction on Feras are looking at us right now through their own telescopes."

"I doubt it," she said, and looked into the eyepiece.

"Why not?"

"The Ferran moon is over ten times brighter than ours," she said, without taking her eye from the telescope, "You can read a newspaper by it. With the moon up, it's hard to see anything else in the sky, and even if the moon is new, the sky is cloudy at night in Solomon."

"Never mind," I said.

"Here is the Nemesis Nebula. After Nemesis the daemon, may his travels be unending."

"You're a Nemesist?" Quayam said.

"I am."

"What's a Nemesist?" I said.

"A Nemesist follows the teachings of Nemesis," she said.

"Nemesis the daemon?"

"Nemesis discovered Olympia," Quayam said.

"He did," Maria said, "He, or she if you prefer, teaches that a life of exploration is the most gratifying an intelligent being can hope for."

"Why is that?" Quayam said.

"The satisfaction of curiosity is the purest and strongest of intellectual pleasures."

"Is that so?" Thristen said.

"Isn't that tautological?" I said.

"No," Maria said.

"But if-,"

"Must you? I am content with my beliefs, and I am sure you are content with yours. I have had this conversation too many times to enjoy it."

"Oh."

"Okay," Quayam said, "Let's look at something else through the telescope."

"Good idea," Maria said.

I said, "I was just trying to understand what you were saying. I wasn't trying to argue with you. Why does it work for you this nomadic lifestyle?"

She frowned at me. "All right, then."

She stepped back from the telescope, looked at the sky for a moment, and then faced me. "Each day, if we see the same things, we stop seeing them. We walk into our house, or our church, and it is the same house, and the same church, with almost everything in the same place, and the same color, and rendered in the same style, as when we last saw it. If we take the time to look at it, we might see something new in these objects, something that speaks of the challenge of creating it, or the intent of its designer, or a detail we had overlooked before, but invariably we do not take the time, because we always have something to do.

"In fact, the more we stay in one place, the busier we get. We have any number of routines to go through. To compete with other people in our stationary society, we have to ration our time. We have to work all day, we have to keep our house, we have to keep our social engagements, we have to concern ourselves with local government.

"But when we travel, what we see is new. We look closely at it. Our instincts demand that we look closely so we can be sure the new things we see are not dangerous. We have no routines, or hardly any, and no standing engagements. To compete with our fellow travelers, we must sleep well, eat well, be healthy and alert. But we do not devote our lives to work. Nor do we worry about being disliked or rejected. There is always the next place, where we can do better. We do not worry about the mistakes we have made, because there is nobody around to suspect us of making them again, there is only us, telling ourselves to do things differently.

"We think new thoughts when we travel, because we must think them. We cannot do everything the same every day. We are stimulated and we cannot help ourselves."

She paused.

"Does that answer your question?"

"It does, thank you," I said, "You have given me a lot to think about."

"And me," Thristen said.

"Good." She turned back to the telescope.

I enjoyed her speech, but I cannot say that I agree with her. I make every effort to enjoy my home and friends, and I think I meet with some success. I can say with confidence that Quayam and Thristen are successful. Nevertheless, I know what she means. We all love to travel.

And so we proceeded south through the desert, every day taking me farther from my daughter. I could have turned back if I wanted to, leaving Quayam and Thristen to continue alone. Quayam assured me that they would understand, but that I should keep in mind that he and Thristen had embarked upon the journey thinking that there would be three of us, and my leaving would be a blow to their confidence.

One day I was so distraught that I burst into tears while talking to Romayne. I was sitting in our tent, and it was just before supper.

"Don't cry, Mom."

"I'm sorry, I don't know what I am doing going on this stupid expedition. Richard Crockford should learn to look after himself. He'll probably get away on his own, and this will all be a waste of time."

"Well I miss you, so why don't you come back?"

"What will I do at home? You go to school all day. I'd be sitting around going crazy."

"You can get a job."

"This is my job."

"My friends have mothers who stay at home, why can't you? You can do whatever they do while my friends are at school."

"Experience has shown that I don't like to do what they do."

"My friends parents can't understand why you're leaving me alone for a year."

"Tell them to go jump in a sewer."

I should say that jumping into a sewer in Pakesh is not a matter of being covered in excrement, but rather of being vaporized by an atomic space bridge.

"They're my friends' parents!"

"They're just jealous because their kids think we're cooler than they are."

"No they don't."

"Yes they do! Why are they always coming over to our house when we're home?"

"Because you let us do whatever we want."

"I do not!"

She said nothing.

"I'm the only mother you've got."

"Don't get so upset, Mom."

"I can't help being upset."

"Well go and talk to Dad, then, because I know you're not coming back, you're just trying to make it look like you miss me, when really you're having a great time being away from me."

I took a deep breath.

"I should not have spoken to you when I was so upset, but please believe me that I miss you, and that I have been miserable trying to decide if I should go back or not. One day you will be in the same position, and-"

"No I won't, I'm never going to do what you do when I have children."

"I think you'll be surprised at how much you turn out to be like us. You may even do the same work as us, although I hope not. And when you do, I want you to have me as an example of the right way to handle these problems. So I'm not coming back, because I have a job to do, and if people like me have to choose between giving up their work and having children, then we will become a dying breed."

"What are you talking about?"

I took another deep breath.

"I don't know. You're right, I don't suppose I'm going to come back, and I should just shut up about it. You're father is going to be furious at me for talking to you like this."

"Maybe it's a good thing you're not here, because now I can grow up to be someone I want to be, instead of like you."

"Well, there you go."

I rubbed my eyes. I had a headache. The bridge sat in a small box on my lap, with a conical tube emerging from it, the wide end facing upward.

I said, "How was school today?"

"Okay, I did well in my math test, and Mina asked me to come to her father's birthday party."

She proceeded to tell me all about her latest social drama, to which I listened with enthusiasm.

"So I'm going to tell here that I can go to her party if she will let me bring Shirin."

"That's a very diplomatic solution, I'm proud of you."

"Well, I have to go, supper is on the table. I hope you cheer up. Talk to Dad."

"I will. Take care."

"Bye."

As I predicted, Quayam was not pleased when I told him about my conversation with Romayne.

"Don't let her see you like that."

"That's the way I am, why shouldn't she see me like that?"

"It just makes it more difficult for her."

"Is it really my responsibility to make things as easy as possible for her?"

"Easier, at least."

"Well, I feel better now, and she seemed fine when we said goodbye."

He put his arm around me. We were sitting by the fire waiting for our supper.

"We're going to have a great time, darling. Don't worry about anything. Just enjoy yourself. You're talking to her twice a day for half an hour. Most parents don't talk to their kids that much in a week."

I put my head in his lap and closed my eyes.

When we arrived at the site of the conjunction, the celesti had already arrived. Three days before it had descended from outer space in the middle of the night and landed in the desert in the same place it had landed every fifteen months for over a thousand years. I have never seen a celesti landing, but I am told that they always do so at night, and that when they descend they are odd-shaped lumps about twenty meters across. Once on the ground, they start to grow and flatten out. This one was fifty meters across and ten meters high, an amorphous mound of conjured matter mixed with sand picked up from the desert. It was surrounded on all sides by a city of tents. There must have been a thousand tents, so that the collection appeared to be a town in itself, with a strange hill in the middle. Colored pennants on high poles flapped in the wind. Maimonidese told me, as we approached the encampment, that each pennant was unique, and would guide you to its owner. When we were within a hundred meters of the tents, we could see the many animals corralled between them, and hear the cacophony of their combined voices.

"Where are you going to stop?" I said.

"It is good to find a place near water, and not too far from the place of rubbish, but if we want to find new business, we must be near the celesti."

Maimonidese steered his wagon around the north of the city, and when we were on the west side, he stopped and declared that we had found our place. I jumped off his wagon. Several men walked briskly from among the tents towards us, and were soon in conversation with Maimonidese, who remained seated on his bench. The rest of the wagons pulled up and we began to unload our tents.

We arranged the wagons in a circle, with a gap for an entrance. Next to the entrance we erected a thirty-meter pole with Maimonidese's pennant on top. It was a yellow triangle with a red star in the middle. To plant the pole securely, we rented a boring tool from one of the men who had been talking to Maimonidese. Thristen and I used it to make a ten-centimeter hole two meters deep in the sand and gravel.

We corralled the horses in one half of the wagon circle, and we pitched our tents in the other half. Most of the merchants, with the exception of Maimonidese, slept in their wagons. The guards, the cook, and we slept in the tents. With the camp arranged to Maimonidese's satisfaction, Quayam and I went in search of a bath, leaving him to settle his contracts with the water and sewage people. We left our armor and weapons in his wagon.

Dirt paths served as the streets of the city of tents. They were winding and random, and took us between the caravans, each of which had made its own camp much as we had done, although most of them had no wagons, and camels instead of horses. The camps were bordered by corrals and by the backs of large tents made of thin cloth, open on the side facing the camp, but closed on the side facing the path. The ground we walked on was sand mixed with pebbles. Gusts of wind flapped the tents and bent the pennant-poles, but raised hardly any dust. The air smelled alternately of cooking fat and animal dung.

Quayam stopped outside a large black tent and read from a sign over its entrance, "Mahsoud Disposal, ten cents a kilogram, all materials."

Inside, we assumed, was the same arrangement used in Pakesh to dispose of sewage, except that in Pakesh, the sewage man carries his apparatus to your house in a wagon. The heart of the apparatus is a large, atomic space bridge into which you throw your garbage. The other side of the bridge is somewhere else, at the disposal company's base of operations, where your garbage comes out as atomized hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon, plus toxic impurities. It is an explosive mixture. According to Pakesh law, the other side must be at least a kilometer from any habitation.

As we stood there in the path, we heard a sudden hiss inside the tent, followed by a roaring sound, and a cloud of steam rose from an opening in the roof.

"Disposal on the premises," I said, "I'm not sure I'm comfortable with that."

The steam rose into the air to be carried away by the wind. I surveyed the tents and imagined the disaster that would follow an explosion.

"It's far enough from our camp," Quayam said.

We started walking again.

Most of the tents were pitched so that their ropes stayed out of the path, but some, whose owners appeared to care little for the convenience of others, had ropes stretched all the way across. We had to step over them or duck under them as we went. There appeared to be no police, or any form of government in this city, temporary and isolated as it was. It seemed to me that I could answer the discourtesy of the ropes by cutting them, and there would be nothing their owners could do to stop me.

I put my theory to Quayam, and he said, "I don't have a knife, but we could borrow one if you like."

Most people we saw were armed. The desert people carried curved swords, and the merchants had long knives. Four northerners passed by. They wore chain armor and carried maces, and looked drunk. One of them tripped over a rope and cursed, but his friends picked him up and they kept going.

After ten minutes of walking, sometimes in circles, we found a camp of white tents with a sign outside advertising hot baths. We went straight in, and soon after were lying opposite one another in a tub of steaming water, in our own private tent. I breathed a sigh of satisfaction. "In three days we shall be on another planet."

"Where the gods come and go as they please," Quayam said, "and do whatever they want."

"I wonder how that works out."

"We'll see."

"How many gods are living there?" I said.

"Not many. Ten, perhaps, on the whole planet. We won't meet any."

"I bet we do."

We lay breathing in the steam, until the water began to cool. We scrubbed ourselves clean, stepped out of the bath, and began to dry off with the towels the establishment had provided for us.

I said, "How do you say 'Where are the public lavatories,' in Lomese?"

He was looking at the bath water. "I don't know."

"We must find you a teacher as soon as we get to Solomon."

Quayam pointed to the water. "Where do they get so much water out here?"

"Maimonides said the locals bring it. After that, there's a bit of recycling."

"What!"

"Didn't you read the sign?"

"Why should I read the sign? I thought you were reading the sign."

"It'll be fine."

He shivered.

"The water looked clear enough to me," I said.

"It doesn't matter how clear the water was. You can't see those little guys."

"The sign says, 'freshly boiled' so it should be sterile."

He shook his head.

When we left our bathing tent, Quayam demanded to see the proprietor. The man turned out to be a chemist from Pakesh. In answer to Quayam's inquiry about the purity of the water, he claimed to have devised a means to clean dirt and soap out of used bath-water leaving it clean and sterile. He showed us his collection of chemicals, which he had brought with him, and explained how he used them. The procedure was complicated, and not entirely feasible in my judgment, but by the end of his explanation, Quayam appeared to be satisfied, and paid the bill.

It was twilight when we stepped out into the street again.

"Time for supper," I said.

"Let's get Thristen from the celesti," Quayam said, "He was going to take a look at it."

We walked towards the celesti, which we could see occasionally through the tents. As we drew near, I saw someone's head moving around on top of it. "There are people on top."

Quayam looked up. "Thristen is probably there too."

"I didn't know we could climb on it."

"Why not? Who's going to stop us?"

I looked around. There was nobody setting rules about climbing. "Let's do it, then."

I put my hand on the steep side of the celesti. It was springy and rough. I started to climb, and Quayam came after me. Our boots and fingers sunk into the surface and left marks behind. When we stood on top we saw a few people sitting at the west end. I recognized Thristen's broad shoulders among them. "They must have come up here to watch the sunset."

When we joined them, I saw that one of them was a wizard, or so I guessed from his long fingernails and the cigarette in his hand. He was a young man, with a thin beard. Thristen introduced him as Mahsoud.

"You should hear this," Thristen said, "Mahsoud has a new theory about the origins of the celesti. It's pretty convincing."

"Mahsoud of Mahsoud Disposal?" I said.

He nodded.

"Why don't you keep your secondary outside the city?"

"There is no law requiring me to do so."

"Forget the law, why don't you do it like it's supposed to be done?"

Mahsoud looked me in the eye but said nothing. The rest of the group fell silent. It was clear that they expected some kind of a fight, and that they were looking forward to it.

"You burn it as it goes through," Quayam said, "How do you control the combustion?"

"My methods are my own."

I said, "Not when you're next door to me in a town made of cloth tents."

"Come on," Thristen said, "you're being rude."

A crow landed nearby. It called out loudly and walked towards us. Even in the fading light, it seemed to me an unusual specimen, with a particularly large head. Mahsoud turned briefly and looked at it.

I said, "Why don't we hear your theory about the celesti over supper? It's on me. And we can buy some seed for the bird as well."

"No thank you."

"Suit yourself," I said, "Thristen?"

He stood up, frowning. "Sure."

As we climbed down the side of the celesti, Thristen said, "What's the matter with you two, did you have an argument?"

"We're hungry," I said.

"That's no excuse for being rude to that guy."

"She invited him to supper, didn't she?" Quayam said.

"Yes, but who would accept an invitation like that?"

"It's still a free supper, and for his bird, too. I call that generous. She could have broken his neck."

"Now we have to worry about some crow," Thristen said, "flying around and spying on us."

"Worry?" Quayam said, "Why would we worry?"

I reached the bottom and looked up at them. It was almost dark. "What's wrong with picking a fight, anyway?"

Thristen landed beside me. "Insecure adolescents pick fights."

"Well, I say good for them."

"Okay, pick as many fights as you want, but not with my friends. I liked that guy."

Quayam stepped down off the celesti and put his hand on my shoulder. "He liked the sewage wizard, darling, so you should not have been rude to the sewage wizard. Do you understand?"

"I understand."

"So let's eat," Quayam said.

He set off into the city of tents, and we followed.

We ended up at Amorous Ali's Wandering Restaurant, and sat at one of twenty round tables under a canvass roof. We ordered red wine, asparagus soup, and roast meat. The menu declared that all the ingredients were summoned fresh from Olympia through 'divine bridges', by which they meant molecular bridges tuned by agents of the gods.

"Thirty-five dollars for a bowl of soup," Thristen said.

"I'm happy to pay it," Quayam said.

The waiter brought us our wine.

"Quayam and I were thinking," I said, "that our base plan should be to make the entire journey across Lomein secretly, by night. We can hunt for food when we are between settlements, and steal food when we are near them."

"Stealing?" Thristen said.

"Why not?"

"That's not generally the sort of tactic we use to fulfill our objectives."

"So we leave a gold piece behind whenever we steal a loaf of bread."

"That's not stealing."

Quayam said, "Enforced sale at an elevated price."

Three musicians started playing on the other side of the tent. We listened to them while we ate our soup.

"From the information we have," Thristen said, "I don't think we will be between settlements for a significant proportion of the time when we are traveling overland in Lomein. Ladan's notes say that it is densely populated."

"We could make a detour," Quayam said, "around the borders, where there are fewer people."

"That depends upon the geography. If the country is bordered by mountains, we may have to go a long way to find an unpopulated route."

"We could go by balloon when we have a favorable wind," I said, "and then protect ourselves from all comers in a building until we get another favorable wind, and then make another balloon, and so on all the way to Foo-Yun. We would get there so fast, Richard's captors would never know we were coming."

"They would see us land," Quayam said.

"Not if we landed at night."

"I don't like flying at night."

"I think it's a good idea," Thristen said.

"When we get there," Quayam said, "we will probably be able to figure out something simpler. The rescue has to follow the journey; otherwise there is no point in making the journey in the first place. The travel plan must not interfere with the rescue plan. The two plans must complement one another."

"It's a complementary planning situation," I said.

By the time we had paid the bill, we had proposed so many promising plans, that to me, with a few glasses of wine and a glass of brandy inside me, our job appeared to be as good as done. We walked away from the restaurant well-satisfied with ourselves and with our meal. When we arrived at our camp, we found Maimonides and Maria sitting out, smoking tobacco from a water pipe. We sat down with them, and got to talking about astronomy.

"How about the sewage-wizard, Thristen?" I said, "He had a theory about the celesti."

"Oh yes."

"Let's hear it," Quayam said.

Maria said, "There are as many theories about the celesti as there are celesti themselves."

I nodded. "I'm sure there are, but let's hear the wizard's theory."

"Let me see if I can remember it properly." Thristen put down his wine glass. "First of all, the celesti connect only worlds with gravitational conditions similar to our own, and atmospheres similar to our own. Some of the worlds have alien plants and no animal life. The plants are the same on every new world we find. When we introduce our own flora and fauna, they take over from the alien ones. And daemons wandering around in space have encountered other, larger beings that appear to be relatives of the celesti."

"That is true," Maria said, "Nemesis himself confirms it. We call them former-celesti, while the ones we encounter on earth are joiner-celesti."

"There we go. He said the former-celesti probably go to new worlds and modify them so that they are ready for life, and leave the alien plants to preserve the atmosphere."

"That is well-accepted," Maria said.